In our second blog post for the s.a.m@PAM series on art conservation, where Science and Art Meet @ the Portland Art Museum, graduate intern Karen Bishop discusses caring for a special bronze bust.

Time has taken its toll on the highly polished bronze surface of Constantin Brancusi’s A Muse. Dark oxide corrosion, fingerprints, and uneven cleaning have all left their mark on the once uniform and reflective finish. In an effort to return the surface to its original splendor, the sculpture is currently undergoing treatment in the Conservation Lab here at the Museum.

Documenting a work of art’s condition before and after treatment is an important part of the conservation process, so to start things off, A Muse was brought into the Museum’s photography studio where a variety of images were taken to capture its current state. This was no small feat, as the sculpture’s round and polished surface acts like a mirror, reflecting everything in the room around it—camera and lights included. A light tent and strategically hung sheets of white paper were utilized to minimize this effect.

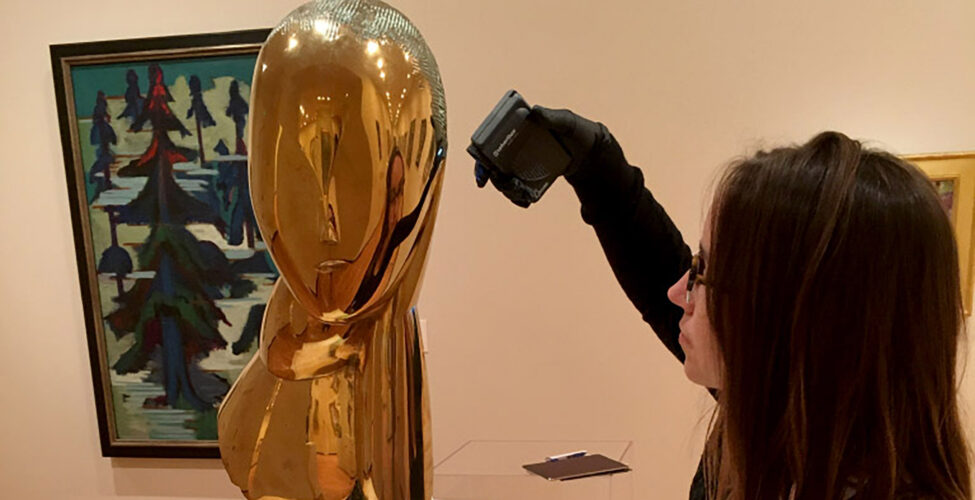

Before starting a treatment, conservators gather as much information as they can on a work of art. This includes researching the artist’s working methods, conducting scientific analysis on material, and reaching out to colleagues who have worked on similar projects. While looking into other works by Brancusi, it was revealed that a similar bronze Muse in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston has thin sheets of gold leaf applied to the hair, a technique known as gilding. Since PAM’s Muse was cast around the same time, it was possible Brancusi experimented with using gold on this version, too. Shimmering flakes could be seen in the recesses of the hair when viewed under a microscope, but to be certain this was not just a metallic paint made to look like gold, Dr. Tami Clare from Portland State University brought over a portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer to analyze the surface of the sculpture. XRF is an analytical technique used to determine the elemental composition of a wide variety of materials. It was an exciting moment to learn it was in fact gold! The same technique was also used to analyze the metallic composition, or alloy, of the sculpture.

Concern for the surface appearance of A Muse began with Brancusi himself, who was known for meticulously finishing and polishing his works by hand. Aware of the natural tendency for bronze to oxidize and develop a dark patina, Brancusi instructed his collectors to wipe down the polished surfaces regularly in order to keep their luster. The current surface condition of A Muse, however, requires more than a cloth cleaning. Polishing is necessary to remove the dark brown patches of corrosion and fingerprints that have etched into the surface. Polishing is done using a specially mixed slurry of fine abrasive particles to slowly remove oxidized particles from the surface of the metal. Once polishing is complete, the overall smooth surface of A Muse will look brighter and more uniform, bringing the appearance closer to how Brancusi originally intended.

Join us on August 8th at noon on our YouTube Channel for a YouTube Live event where you can ask me about how we balanced the preservation of the original bronze material and provided a unified appearance in Brancusi’s A Muse.

View A Muse in Online Collections

Karen Bishop is a second-year graduate conservation student focusing on objects conservation at SUNY College at Buffalo State. She is spending her summer interning with conservator Samantha Springer at the Portland Art Museum where she is working on a variety of projects, including research and treatment of Constantin Brancusi’s A Muse. Internships are an integral part of conservation training, both before (pre-program) and during graduate school.