Some introductory copy explaining what’s in the gallery space. Adipiscing, aliqua minim ipsum duis. Ipsum duis eiusmod nisi. Eiusmod nisi ea nulla. Ea nulla pariatur culpa, officia elit adipiscing. Culpa officia elit adipiscing. Elit adipiscing exercitation id dolore commodo. Exercitation, id dolore commodo.

Mirror Mirror: Silver in the 20th century

Silver has had special status in European and world art for thousands of years. Besides coins and jewelry, silver was used for objects of practical use, and families often held their wealth in a collection of silver spoons, teapots and other items. When stainless steel, aluminum and titanium became common, the meaning of a family hoard of silver plate shifted. At the same time new industrial uses of silver were discovered, as medical antiseptic and above all, photography. Artisans still make everyday objects out of silver in new and creative ways because the soft, warm, clear and reflective surfaces have enduring appeal. In this gallery modern silver is paired with silver print photography to demonstrate how radically the use and appreciation of silver has changed.

This display highlights the gift of Portland native Margo Grant Walsh, who donated nearly all the modern silver in the Museum’s collection.

For the Enjoyment of All: Celebrating the Kress Gift

In 1952, the Portland Art Museum was given a spectacular selection of European art by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation in New York. The department store magnate Samuel Kress, who had assembled a vast collection with the advice of noted scholars, decided to disperse his works among art museums in cities where his stores were located. Portland’s gift included many important early Italian works with religious subjects, which were not typically collected by US public museums at the time. This exhibition celebrates the generosity of a scholarly collector and donor, and represents the first time all of Kress’s gifts, including the works added by Kress before the gift was finalized in 1961, have ever been shown together.

The group was not assembled unilaterally, however. The Foundation invited the Museum to propose a theme around which a gift would be assembled. Museum staff focused on the Renaissance and selected six subthemes: Unity in Narration; The Rise of Landscape Painting; Revival of Classicism; Interest in Anatomy; From Symbolism to Naturalism in Religious Art; and Portraiture. The Kress team then offered additional works and even purchased some art to give the gift more impact.

American Land

Landscape painting has always had a unique place in the history of American Art. Earlier settlers and colonists especially celebrated the American landscape – one that has been shaped by the stewardship of Native peoples through the ages. For many Europeans, however, civilization, cities, and the memory of Greece and Rome were key ways of understanding the world, and the presence of Native people in the American landscape was largely dismissed. The American landscape paintings in the museum’s collection capture the full breadth of the country’s history and relationship to land from the settler’s point of view, ranging from the earliest Hudson Valley painters, to the works of Americans abroad and the urban landscape.

Since long before colonists arrived, Native people have continued to live in communion with these same lands despite their violent displacement through the forces of colonization. This gallery includes contemporaneous works of Native art that reflect their connection to the natural world and also demonstrate how Native artists transformed what they gained through global trade into their aesthetic systems.

Highest Heaven

The glorious saints and archangels in this gallery were made in the Americas but far from the United States. Elvin A. Duerst’s gift of works from the Spanish viceregal or colonial period in Central and South America from 1521 until the revolutions led by Simon Bolivar liberated these areas from Spanish control in 1821. Oregon-born and educated Duerst was an American foreign aid worker who spent years in Central and South America where he assembled much of his collection. This art represents a tradition rarely present in US museums but familiar to millions from Peru, Chile, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, and Mexico. The violent conquest of the Americas by Iberian powers, beginning in the sixteenth century, did not displace the peoples of the Incan and Aztec empires. Artists and artisans applied their advanced skills to the new religion of Christianity, producing an iconography and style completely new and reflective of their ancient cultures. The Duerst gift is shown here along with other examples of Ibero-American art of that period, as well as examples of pre-contact works in ceramic, textiles.

Mystic Mountain: Mount Hood in Art

Mount Hood’s iconic form, isolated presence on the horizon, and impressive height all serve to mark the natural monument as home for Portlanders. It has inspired generations of artists, from Childe Hassam and Albert Bierstadt, to Sekino Jun’ichirō, who recognized its affinity to Japan’s Mount Fuji when working here in the 1960s.

In 1890, Northwest author Frederick Balch, who had extensive experience with local tribes published Bridge of the Gods, in which he claimed to tell the Native story of the mountain. His tales have never been corroborated, and in fact serve as a kind of erasure of Native knowledge. The Native peoples of the river valleys had decades prior been forcibly removed to the arid lands adjacent to the mountain, established as the Grand Ronde Reservation in 1857 and Warm Springs Indian Reservation in 1855. In Balch’s account Mount Adams and Mount Hood were sons of the Creator, and their eruptions were expressions of their rivalry for a beautiful woman. In a later theatrical production of the book, Mount Saint Helens became Loowit, Mount Adams was Pahto and famously Hood became Wy’east.

Facing Ourselves

Portraiture is about truth and honesty, both in how we choose to have ourselves portrayed and in how artists present their subjects. During the Renaissance, portraiture was tied to humanism, which values the individual. Artists sought to recover the art of portraiture known from Greek and Roman antiquities. We all like to embellish, however, and the Roman examples in this survey of the Museum’s European and American portraits are stylized and simplified. Maybe all portraits are about relationships and the intensity of the encounter between artist and subject. Not every portrait is a picture, however.

This gallery features European and American art in photography, painting and sculpture. It includes epitaph inscription slabs from ancient Roman tombs, a coat of arms, and a reliquary. The works in this gallery represent the diversity of our community as well as of our collection, and span thousands of years, and many continents and are done in many styles. They also challenge our idea of what we understand by Europe – proud Syrian Romans in togas, for example, speak to us from their tombstones, in Aramaic.

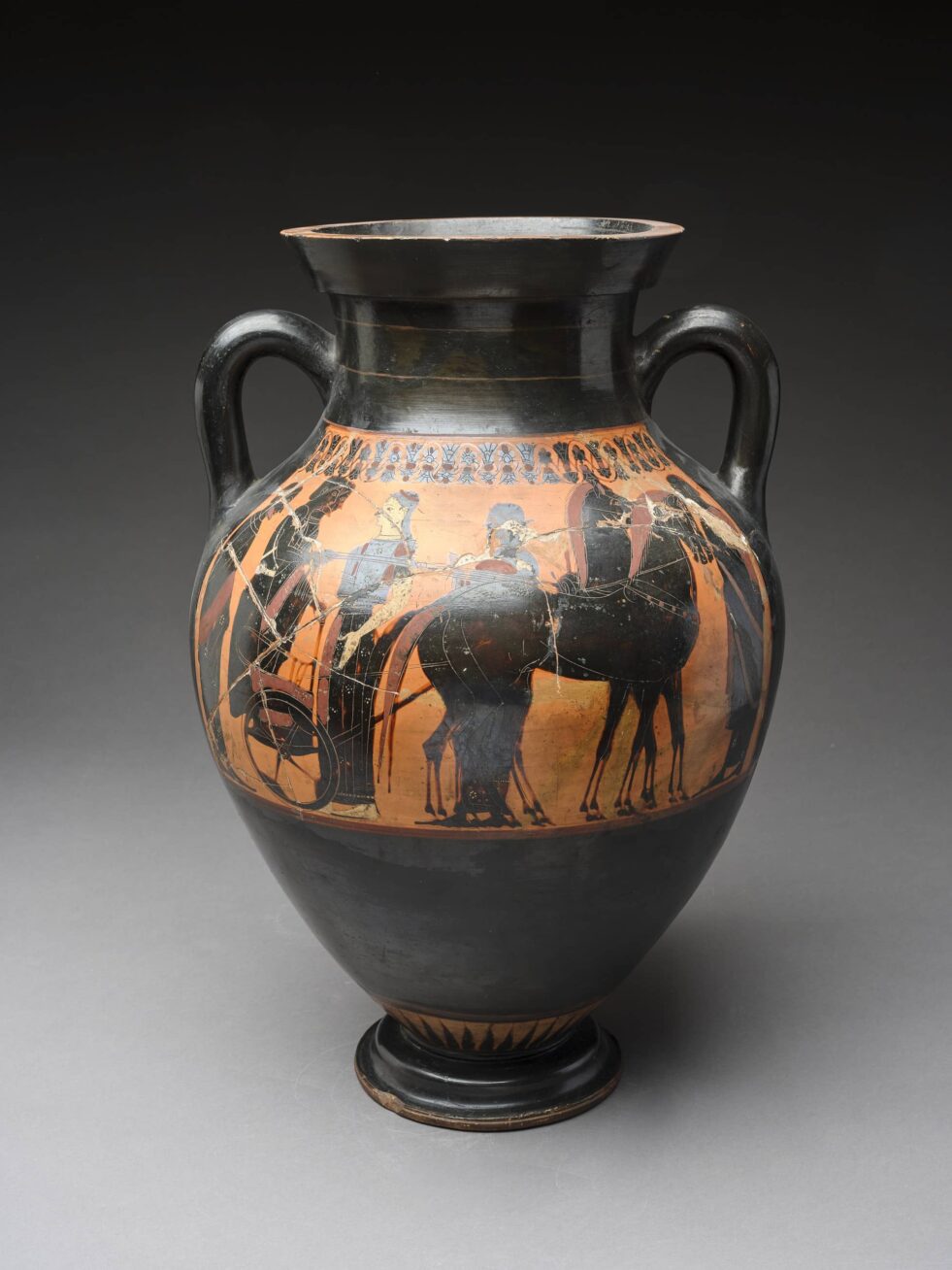

Myth and Memory: Mediterranean Antiquity and its revivals

The ancient Greeks loved wall murals and small portable paintings, but most of these have been lost over time. Instead, their art is best known from objects such as ceramic pots and vessels, excavated from rubbish heaps and graves. These ordinary household wares were produced in vast quantity, and some were even decorated by artists of extraordinary talent. Those that survive, often reconstructed from shards, continue to inspire artists and all of us with the stories and culture of ancient Greece and Rome. The stories range from the labors of Herakles to the poet Orpheus, and range in time from Greek antiquity to the age of Pablo Picasso. Here, we can see how later artists have interpreted those eternally relevant stories and themes for their own generations.

Global Impressionism

In 1874, a group of French artists organized the first exhibition of sketch-like avant-garde paintings at a private gallery in Paris. Critics gave them the unflattering label “Impressionist” because of their sketchlike works, but the artists embraced the terms and exhibited under this name for another seven shows. Their use of broken strokes of often pure color, is often seen as typically French but in fact became a global phenomenon. This gallery celebrates this long-lasting movement and its impact, all the way to Portland. Impressionists focused on what their champion, the influential critic Charles Baudelaire, identified as modern life, and painted scenes of the harbor and coast, industry, city life, and nature.They embraced the workings of a bustling modern city as well as the rural landscape, alert to the patterns or forms of constant change they could capture with their brushes.