The divide between the rich and the poor has been a fundamental aspect of the human condition through virtually all ages and cultures. These paintings show two French families from opposite ends of the social spectrum during the last half of the 1600s. Their portrayals reflect the vast differences in their lives, and raise questions about the motivation of artists to depict poor people.

Nothing is known about the circumstances surrounding the creation of each painting, but it is nonetheless clear that the relationships between the artists and the people they depict were fundamentally different. The rich family hired Gabriel Revel to paint their portrait and paid him well considering his ability and reputation. So, he wanted to flatter them in the hope of gaining other work from them or from their friends. Jean Michelin’s painting is not strictly a portrait because peasants could not afford a work of art. It is possible that the people were created from the imagination of the artist, but it is more likely he sought out peasants, who would have welcomed a modest fee for posing.

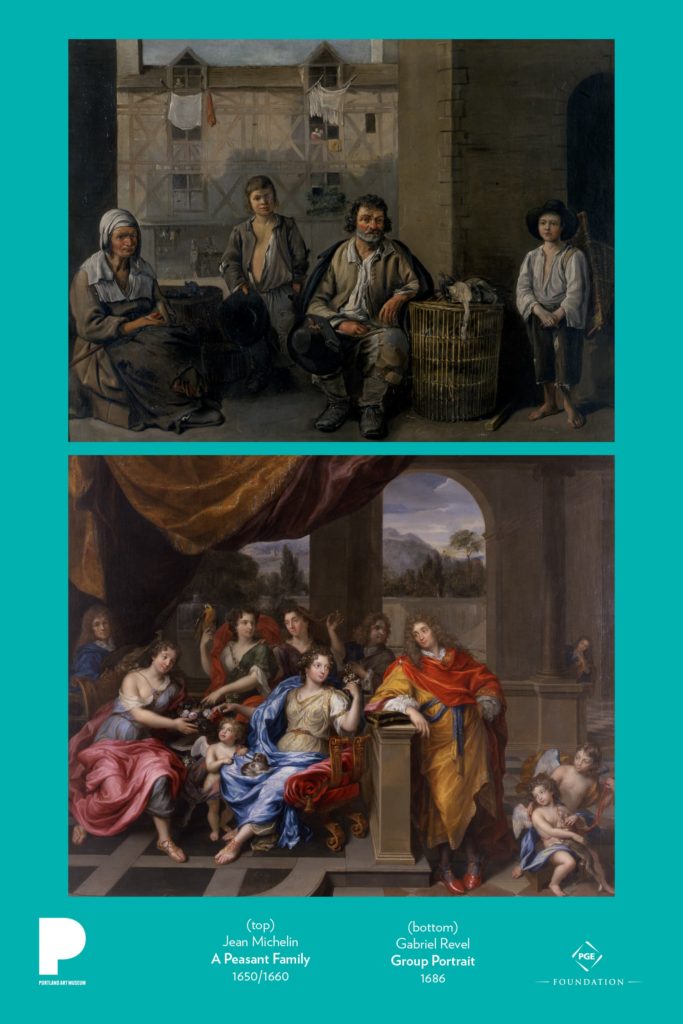

Gabriel Revel, Group Portrait, 1686

The painting shows a festive gathering of a family belonging to the aristocracy, the highest social class. The opulence of the palatial setting, their sumptuous, colorful clothes, and their attitudes suggest that they were members of the nobility, those families holding hereditary titles, such as duke, count, baron, or lord. Often large landholders, the nobles were the smallest social group, but held most of the wealth of the country and wielded power over the lower classes.

The family is situated on the terrace of a palace with splendid architecture and a large garden with a fountain and a grand staircase. The composition centers on

the man and woman at center, presumably husband and wife, exchanging loving glances. The children are likely the product of their union. The three other ladies are surely relatives, perhaps sisters of the husband and/or wife. The people on the fringes of the group—the lute player at left, the man behind at center, and the woman peeking into the scene at right—might be relatives, but they might also be retainers, people employed by and close to the family, such as a tutor or governess.

The adults in the foreground are dressed in whimsical attire based on ancient Roman dress, and the children are depicted as winged cherubs. One might think that it depicts a costume party, but the French enjoyed alluding to their Imperial Roman ancestry in portraits (France was the territory known as Gaul in the Roman Empire). There are numerous portraits portraying French aristocrats as mythological gods, and here the wife and her female companions were almost surely meant to allude to Venus, the Roman goddess of beauty and love, and her attendants, the Three Graces.

The noble family’s animals—two dogs and a parrot—are likely portraits of favorite pets. The dogs also symbolize fidelity in keeping with the happy marriage being celebrated. In the seventeenth century a parrot was a marker of status, a living counterpart to the pearls, jewels, and luxurious clothing. Parrots conveyed not only wealth, but also sophistication because they were imported from Africa, Asia, and increasingly Central and South America.

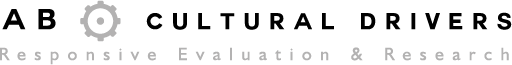

Jean Michelin, A Peasant Family, 1650-60

In seventeenth-century France, peasants made up the vast majority of the population and most lived in poverty. Michelin shows this family trying to eke out a meagre living by selling poultry on an urban street. They could not afford to live in town and would have travelled from the countryside or from slums on the edge of the city. Their impromptu shop in a public arcade is contrasted with a proper store in the timber-framed building on the other side of the street. It has a counter, and the poultry has been carefully displayed to attract business.

Clothing was an even greater signifier of social status than it is today. In contrast with the fine fabrics worn by the rich family, the peasants’ attire was made of coarse cloth almost devoid of color because dyes were costly. As is clear from the many patches and ragged edges, the poor had to wear clothes until they disintegrated.

Free education for all did not begin until the late 1800s in France. In the 1600s, poor children had to work, as is made clear by the basket—a predecessor of the backpack—worn over the shoulder of the boy at right. He was expected to tote goods into town and to make deliveries.

A peasant family’s relationship with animals was markedly different from the rich family’s. The poor existed with chronic food insecurity and could not afford to keep a pet. Even a working animal, such as a hunting dog or a horse, was likely impossible for them. Their animals were raised for food, principally to sell rather than to eat themselves. On the rare occasions when the impoverished were able to consume protein, it was limited to coarse bacon or perhaps poultry on special occasions.

Michelin depicts the peasant family with sensitivity and compassion. They regard the viewer directly with faces that bear the hardened look of people whose living is precarious, but their expressions are without malice. Although torn and tattered, their clothes are clean and they project dignified attitudes that contrast with the distracted frivolity of the rich family.

At the time of its creation, A Peasant Family was a novel type of painting in France. The realistic depiction of ordinary people had not been considered a worthy subject before the late 1630s, when Flemish and Italian paintings depicting common folk cavorting in taverns began arriving in France. These paintings usually feature rude and rowdy behavior that was meant to amuse and instill a feeling of superiority

in the well-to-do patrons who bought them. A different approach was taken by Antoine, Louis and Matthieu Le Nain—three brothers working in Paris in the 1640s—who invented compassionate scenes portraying peasants as sober and quiet. Michelin satisfied the demand for such paintings slightly later.

Unfortunately, there are no written accounts about such paintings of the poor from the 1600s to help us understand what they meant to contemporaries who could afford to buy them. In general, the middle and upper classes considered peasants as vile savages or wild beasts. They were held to be the cause of a variety of

social problems, most especially epidemics and riots at times of famine. For more progressive members of the upper classes, peasants exemplified traditional values, such as industry, endurance, and piety, but this was a comforting myth in the brutal reality of the period. It seems most likely that the collectors who bought paintings of the poor were motivated by Christian faith to feel sympathetic to their plight.

Discussion and activities

- Create a list of paired opposites that describe the differences between these two paintings. (Think about color, composition, mood.) Then, create a list of words or phrases describing what the two pieces have in common. Ask students to compare and discuss their lists in pairs or with the whole class. What do these paintings share? What makes them different? Imagine a dialogue between the figures in each of these paintings. What would they say to each other?

- How do these paintings represent narratives of power? Identify details in each painting that suggest degrees of power or powerlessness. How does power intersect here with class, gender, age, race, or other elements of identity?

- Compare images of poor and working people from the seventeenth century with those made by nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists. (Find examples in the Poster Project.) How have the motivations of artists changed in relation to such subject matter?

- Create a portrait of your own family in any medium. What is most important for you to convey about your family? You might focus on individual personalities or relationships, where they live, or activities they like to do together. Think about setting, dress, positions, props, pets. Would the portrait be realistic or include elements of fantasy?

Spanish-language PDFs developed with the support and collaboration of