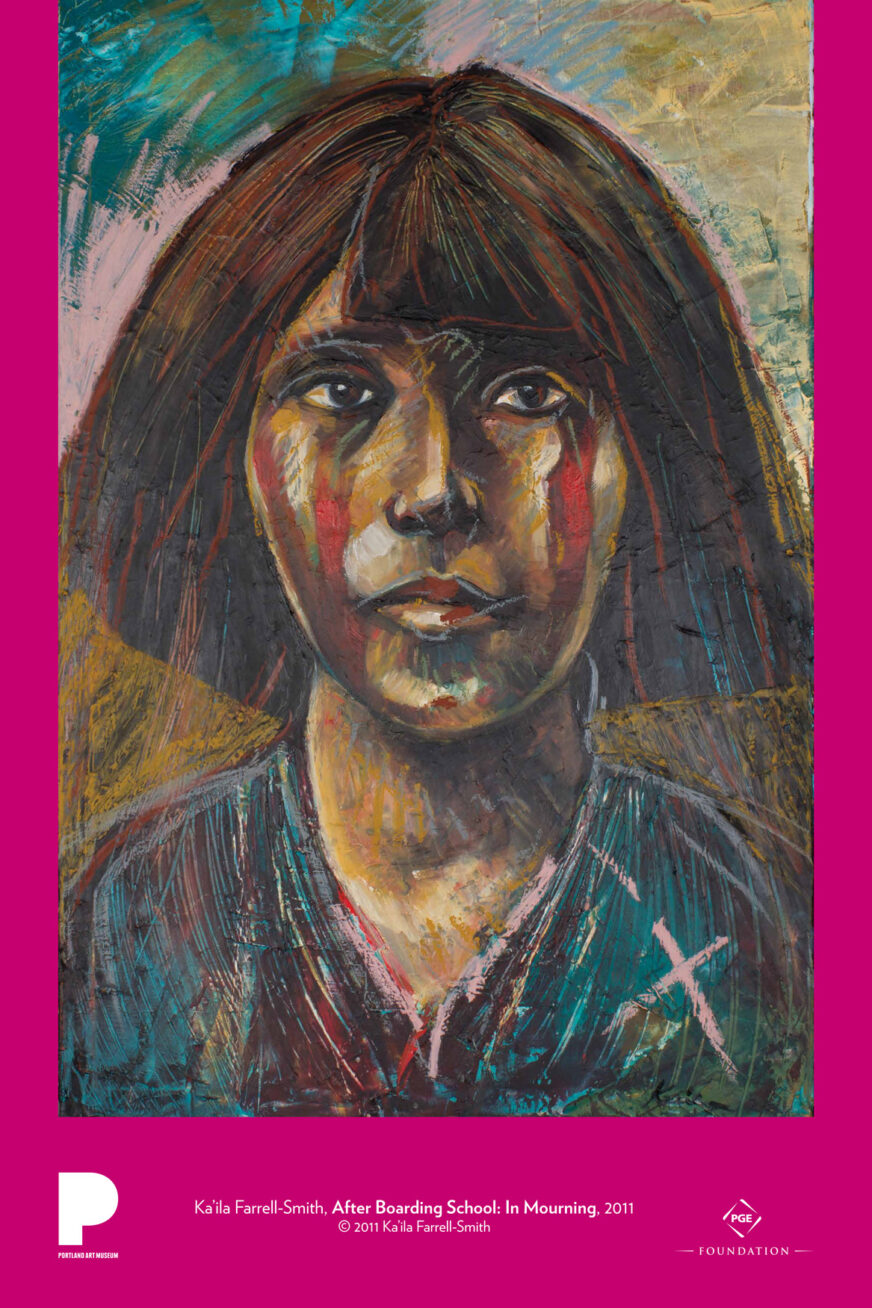

Ka’ila Farrell-Smith is a contemporary Klamath/Modoc visual artist based in Portland, Oregon. This painting honors the experience and survivance of Indigenous children who were taken from their families and forced to attend Indian boarding schools.

Indian boarding schools’ purpose was to achieve the full assimilation, or absorption, of Native American children into dominant, U.S. culture. The first Indian boarding schools were established in the United States in the 1870s. At the time, the United States was concluding a series of brutal wars against Indigenous people of the Great Plains and forcing the last independent tribes onto reservations. White reformers promoted the boarding schools as an alternative to genocide. But violence infused the philosophy of the schools: “Kill the Indian and save the man” was the motto of U.S. Army Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt who led the Indian boarding school movement and whose earliest pupils were prisoners of war.

As Pratt’s words suggest, boarding schools were designed to systematically destroy students’ Native identities. Schools were located far from students’ homes to remove the influence of families and tribes. When students arrived, their long hair was cut and their clothes destroyed. Students were forbidden to speak, dress, or pray in their ancestral Native ways. They were required to speak English, to convert to Christianity, and to adopt white American customs or face severe punishments. They were taught to hate Native cultures as savage and revere U.S. and European cultures as civilized. Many students were deeply homesick. Many also died of disease while at school.

Ultimately, over 100,000 Indigenous children were forced by the U.S. government to attend boarding schools. Many of the schools were dismantled after a 1928 government report revealed abysmal conditions at the boarding schools: students were “malnourished, overworked, harshly punished, and poorly educated.” These historical traumas have deeply impacted generations of Native American families and cultures to this day.

Farrell-Smith’s painting, After Boarding School: In Mourning, references a photograph by Edward Curtis, Mosa—Mojave, as well as the experience of her own father who was forced to attend a boarding school. Farrell-Smith portrays an Indigenous youth who has survived this experience of indoctrination and colonization. The youth’s hair has been cut off—standard practice in boarding schools, but, in Klamath tradition, an expression of grief and mourning. The painting suggests scars and sad memories, but the bright colors and textures illuminate the vibrancy of healing through remembering. An important step in decolonization is to reclaim and remember Native culture, ceremony, art, foods, language, and family.

The few remaining boarding schools—such as the Chemawa Indian School outside Salem, Oregon—are playing a role in this process of decolonization. One unintended, positive consequence of the schools was that they brought together Indigenous students from different tribes across the country and therefore helped to create a sense of shared, Native identity. Chemawa, founded in 1880, has become a source of academic achievement, empowerment, and pride for Native communities.

Special thanks to Ka’ila Farrell-Smith for contributing to the writing of this poster.

Survivance: a concept developed by the Anishinaabe critic Gerald Vizenor who writes, “Native survivance is an active sense of presence over absence, deracination, and oblivion; survivance is the continuance of stories, not a mere reaction, however pertinent… Survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, detractions, obtrusions, the unbearable sentiments of tragedy, and the legacy of victimry.”

Gerald Vizenor, “Aesthetics of Survivance: Literary Theory and Practice.” Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. Edited by Gerald Vizenor. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2008, p. 1.

Discussion and activities

- In a 2013 interview, Ka’ila Farrell-Smith said, “I am a Klamath woman. It took me a while to understand that there’s this need to return and start looking at my Indigenous identity; looking at how painting explores what that means in contemporary society; how Indigenous people identify with displacement from their ancestral homelands.”

How is displacement explored in After Boarding School? Write down 10 words describing how you think the subject of the painting could be feeling. Use the words you generated to write a short story or poem about the painting. - Farrell-Smith’s painting responds to Edward Curtis’ 1903 photogravure Mosa—Mohave published in his portfolio The North American Indian (available in Portland Art Museum online collections). Compare and contrast the two images. How does Farrell-Smith transform Curtis’ photograph? What roles do texture, line, and color play in this transformation?

- Make a black and white photocopy of a picture of yourself. Using crayons, colored pencils, paint, or found media, add color and texture to your photograph. Try to remember how you felt when the photo was taken, and use your materials to express those feelings.

Recommended resources

- Read an interview with the artist Ka’ila Farrell-Smith

- Ka’ila Farrell-Smith’s website

- Watch a short video of the artist from RAW Artists Media on YouTube

- Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center

- Charla Bear, “American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many,” National Public Radio (May 12, 2008)

- Oregon Encyclopedia “Chemawa Indian School”