On May 18, 1980, an earthquake struck below the north face of Mount St. Helens in Washington state, triggering the largest landslide in recorded history and a major volcanic eruption that scattered ash across a dozen states. The sudden lateral blast—heard hundreds of miles away—removed 1,300 feet off the top of the volcano, sending shockwaves and pyroclastic flows across the surrounding landscape, flattening forests, melting snow and ice, and generating massive mudflows. A total of 57 people lost their lives in the disaster. This anniversary always hits home for me, as I was a 12-year-old living in Spokane at the time. I have such vivid memories of the approaching ash cloud, the bizarre dark skies at daytime, the uncertain fears of inhaling the ash, deserted streets, and closed schools.

— Alan Taylor, “The Eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980,” The Atlantic

In this recollection, journalist Alan Taylor conveys the profound impact that the Mount St. Helens eruption had on the land and on survivors: the massive scale of destruction, the fear, the sense of the world made radically strange and unpredictable. Photographer Emmet Gowin arrived in the Pacific Northwest one month after the eruption. He had received a fellowship from the Seattle Arts Commission to create a survey of the State of Washington and soon realized that the aftermath of the cataclysmic eruption would be his focus. A broad security perimeter kept the public far from the site, but Gowin worked tirelessly to secure permission to fly over the volcano. His photographs chart the stunning effects of the eruption: horizonless forests of felled trees and abstract mudflows dripping down the mountainside suggest a seemingly endless field of devastation and capture nature’s raw and stunning power.

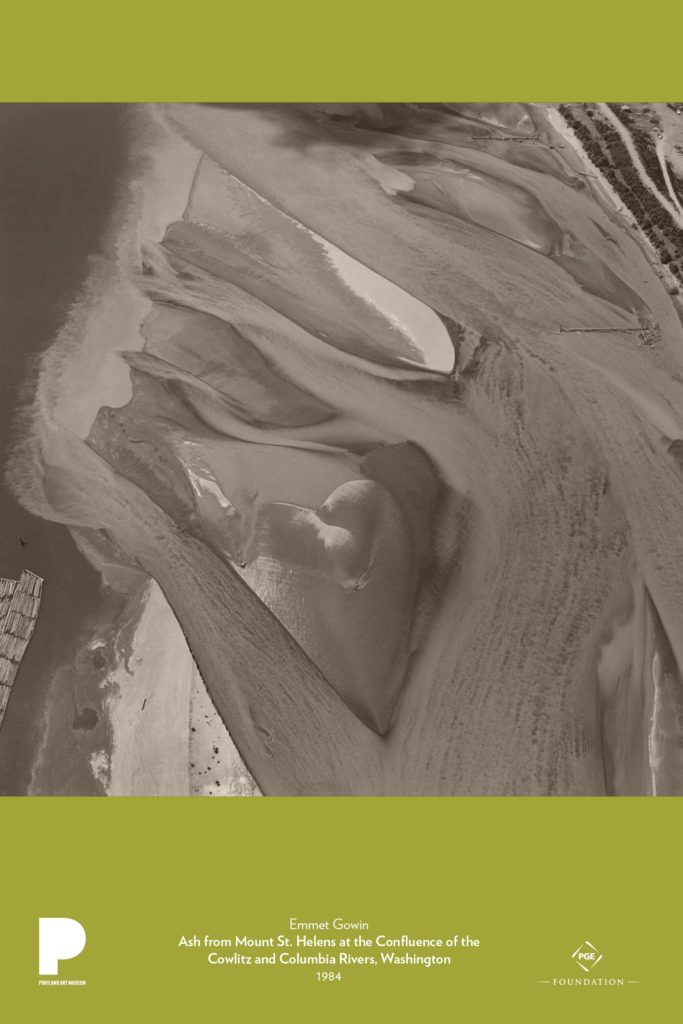

This image of the confluence of the Cowlitz and Columbia Rivers evokes two of the most dramatic effects of the eruption: the fluffy ash, several inches deep, that blanketed the surrounding area and the lahars—violent, fast-moving mudflows resembling wet concrete—that filled the waterways with sediment. Gowin shows the ongoing impact of these events four years after Mount St. Helens erupted. His photograph first draws our attention to the mysterious and disorienting abstract shapes and textures formed by the rivers’ currents, the ash and mud, and the reflection of light on water. Only gradually do we identify recognizable features, such as the shoreline and timber. For Gowin, photographing Mount St. Helens from the air did not produce a sense of detachment or mastery, but of surprising intimacy: “I felt like I was photographing the stomach or the heart, the organs of the landscape. I was trying to show what the beating heart of the landscape was like.”

Gowin had grown up in a devoutly religious family in rural Virginia in the 1940s and ‘50s and returned to the area after earning an MFA in Photography at Rhode Island School of Design. For his early photographs, in the 1960s, Gowin chose subjects that were close to him both physically and emotionally: his wife, Edith, their children, and the extended family. During the 1970s, he expanded his radius into Europe and South America, where he often positioned himself on hilltops to take pictures of the landscape below. His first experience of Mount St. Helens in June 1980 provided a new direction for his work. Over the next five years, Gowin returned periodically to photograph Mount St. Helens from the air as well as the ground, marveling at the sublime beauty of the region, its sudden destruction, and its gradual rebirth. Aerial photography became a mainstay of his practice. From Mount St. Helens, he turned his attention to other landscapes in the West—the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington, the Nevada Test Site outside Las Vegas—that bore the scars of cataclysmic human intervention. Gowin sees promise and warning in the manipulated topography of the earth, and profound beauty there that connects us to nature:

When we really see these awesome, vast, and terrible places, we may tremble at the feelings we experience as our sense of wholeness is reorganized by what we see. The heart seems to withdraw and the body seems always to diminish. At such a moment, our feelings reach for an understanding. This is the gift of a landscape photograph: that the heart finds a place to stand.

Discussion and activities

- Before sharing the title or any information on the photograph, introduce the work through one of the following three prompts—or a combination of all—to encourage close looking and analysis.

- Look closely at the image for 30 seconds. Describe the shapes and textures that you find. What does this photograph portray? Identify any features of the image that orient you. Does this photograph have a right-side-up? Why or why not?

- Print copies of the poster from the PDF available online. Cut the image into squares. Divide students into small groups and give one square to each group. Ask students to infer what the piece is, using their imaginations, then try to put the squares together to form the whole work.

- Science approach:

- Ask students to examine the image and make observations (what do you see?) and inferences (what do you think it is?).

- Then, introduce each of the following pieces of information, one at a time, asking students how they revise their inferences with each new term.

- Mt. St. Helens

- Ash

- Water

- Provide instruction on the geographical processes evident here, such as braided stream systems, erosion and deposition, and the effects of sediment on stream flow. Repeat the observation process after instruction: Now, what do you see?

- Compare this image with other stream systems. How is this different?

- Compare Gowin’s photograph with Google map satellite images of the same region. How are they similar? How are they different? Consider the purpose or purposes of each photograph. What makes one art and not the other, or are they both art? Provide reasons for your response.

- Compare Gowin’s photograph to other works in the Poster Project, such as George Johanson’s Under the Volcano, Wendy Red Star’s Indian Summer, and Charles Heaney’s Mountains. What are some of the differences you notice? How does each artist situate us—the viewers—in relation to the mountain? How does each artist think differently about what it means to represent the landscape?

Recommended resources

- Online Exhibition

- Emmet Gowin on photographing Mount St. Helens

- Observation and Inference

- Perspective and Abstraction

- Clay Fossils Inspired by Mount St. Helens

- Emmet Gowin via ArtNet (photo gallery)

- An interview with Emmet Gowin via Bomb Magazine

- Force of Nature: Emmet Gowin in the American West at The Portland Art Museum

- Lecture: “A Life in Photography” at The Portland Art Museum (video)

- Dawson Carr, PhD, Lecture on Volcano! Mount St. Helens in Art

- Mount St. Helens Institute Classroom Resources, including recommended websites

Text resources

Gowin, Emmet, and Carlos Gollonet. 2013. Emmet Gowin: [Fundación Mapfre, Madrid, May 29 – September 1, 2013; Sala Rekalde, Bilbao, October 24, 2013 – January 29, 2014]. New York, NY: Aperture Foundation.

Available at Crumpacker Library

Brookman, Philip, Emmet Gowin, Jock Reynolds, and Terry Tempest Williams. Emmet Gowin: Changing the Earth ; Aerial Photographs ; New Haven, CT: Yale University Art Gallery, 2002.