Utagawa Hiroshige is one of the most widely recognized Japanese artists. Although he was also active as a painter, he is best known for his designs for woodblock prints. He and his publishers took advantage of a burgeoning new interest in travel in early nineteenth-century Japan, creating many massive series of landscape prints on particular themes. His picturesque compositions helped popularize Japanese prints abroad, and particularly influenced European painters in the late nineteenth century.

Hiroshige was born in 1797 in the city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo) to a lower- ranking samurai family. After his father’s untimely death, Hiroshige took over his father’s position as a fire warden in service to the Tokugawa shogunate; he was only twelve years old at the time. The position gave him a small income and left him a great deal of leisure time. Within a few years he began to study painting in the studio of Utagawa Toyohiro. The Utagawa school, which by this time already had many masters and pupils, specialized in ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world.” This genre of painting and prints had become popular more than a century earlier, and took as its subject the urban entertainments of Japan’s largest cities.

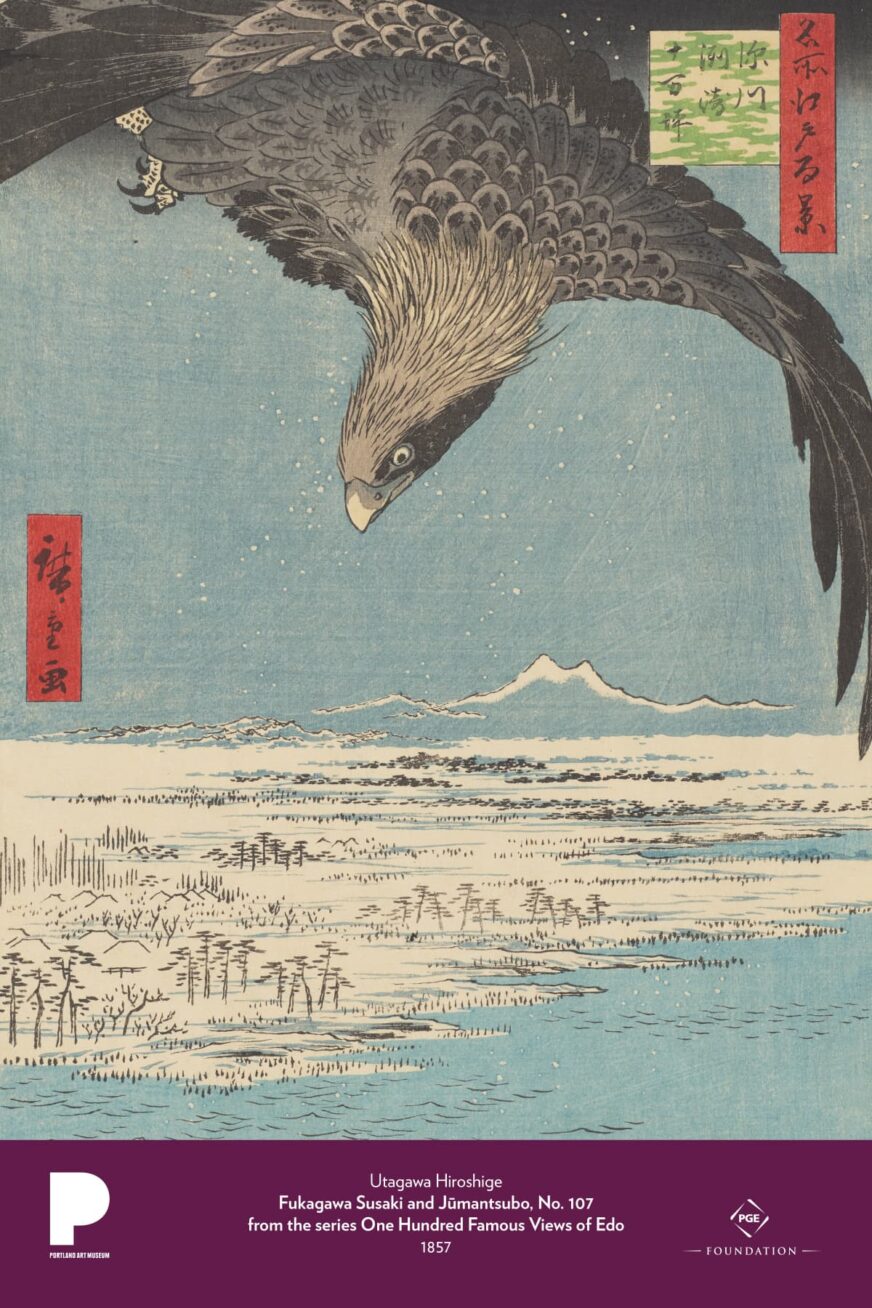

About a decade into his career as an artist, Hiroshige began to produce the poetic landscape prints for which he is best known. This print comes from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo in which Hiroshige took celebrated places in and around the city of Edo as his subject. The most successful designs in this series are characterized by surprising, unconventional perspectives and dramatic cropping. This approach made the familiar landscapes of Edo fresh for Hiroshige’s audiences, who were not used to seeing these well-known places in such novel ways. Fukagawa Susaki and Jūmantsubo is one of the best examples of this approach, and often regarded as a masterpiece within the series.

Soaring high above a frozen marsh, a hawk searches for prey along the shores of Edo Bay. Far below, the snow-covered plain of Susaki stretches into the deep distance. The title of this stark winter landscape, Fukagawa Susaki and Jūmantsubo, was the name of a scenic place known for its vast open plain overlooking the sea. Details of the landscape are rendered in a fairly schematic manner, with lines, dots, and dashes to mark trees, grasses, and other features of the terrain. The white snow is indicated by holding the white of the paper in reserve, with the sky and sea printed in blue above and below. White dots trailing from the sky indicate a lightly swirling snowfall. A dark band of grey at the top of the sky and a band of deep blue at the bottom are achieved by a gradation technique known as bokashi, giving the image a richer sense of depth.

Framed by the hawk’s outstretched wing, the composition emphasizes a sense of distance and dramatic tension. By bringing the viewer up to a height far beyond that of human scale, Hiroshige creates drama by showing us a majestic and impossibly far-off vista. Snow-capped Mount Tsukuba in the far distance even seems small by comparison. At the time, Edo was the biggest city in the world, with a population well over one million inhabitants. Yet Hiroshige reduces signs of human habitation to just a few oblique details: snow-covered roofs a little ways inland at lower left, and a single wooden fishing tub bobbing in the waves.

Every woodblock print created in this period involved a complex process and an entire team of creators. An artist would be hired to produce the design; a carver would carve separate blocks of wood for each color; a printer would take a single sheet of paper and use those woodblocks to build up the image in layers of successive colors; and a publisher would orchestrate the production and market the prints for sale. By 1857, when this print was created, the techniques and publishing system of the Japanese print industry had long since been perfected by generations of craftsmen and savvy entrepreneurs. Here, Hiroshige’s signature was carved into one of the blocks and printed with the rest of the image: it appears in a rectangular red cartouche at left. The publisher is also identified with a printed seal in the left lower margin. Although the carver and printer are not named, they would have been highly skilled craftsmen to produce such a crisp and superb final product.

Discussion and activities

- List five things you notice about this picture. What is our perspective on the scene? How would you describe the composition? What do you notice about the arrangement of forms, the use of space and color, the cropped edges? How do these elements affect the mood of the piece? What feelings do you have as you look at it?

- In this print, the artist Hiroshige portrays a landscape that would have been familiar to people living around or traveling through the city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo), but he approaches the scene from an unusual (at least for humans) perspective. Create a drawing or photograph that looks at a familiar scene from an unfamiliar perspective. You might approach the scene from above (as in this image) or below, very close or very far. What new details, shapes, or colors do you notice about the scene from this new perspective?

- In the mid-nineteenth century, when Hiroshige created this work, Edo was the biggest city in the world, with a population well over one million inhabitants. Yet there are scarcely any signs of human habitation in this scene. Compare this print to iconic images of Portland, Oregon, with Mount Hood floating over the city, or Seattle, Washington, with Mount Rainier in the distance. Compare this print also to Sang-ah Choi’s representation of the American landscape, included in the Poster Project. What are some of the different ways these works ask us to think about the relationships between nature and the city? How do you experience nature in the place where you live?

- Write a story or poem from the hawk’s perspective. Imagine what the hawk sees, hears, and feels. What happened just before this moment? What will happen next?

- Write Around PAM: Utagawa Hiroshige. A writing prompt inspired by Fukagawa Susaki and Jūmantsubo and developed by museum partner Write Around Portland.

Recommended resources

- Objects of Contact: Encounters between Japan and the West. Portland Art Museum. 2020.

- Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. Brooklyn Museum. (This online exhibition displays all 118 splendid scenes from Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. Ours appears as No. 107 in the section “Winter.”)

- Edo. 1849. Geographicus.com, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

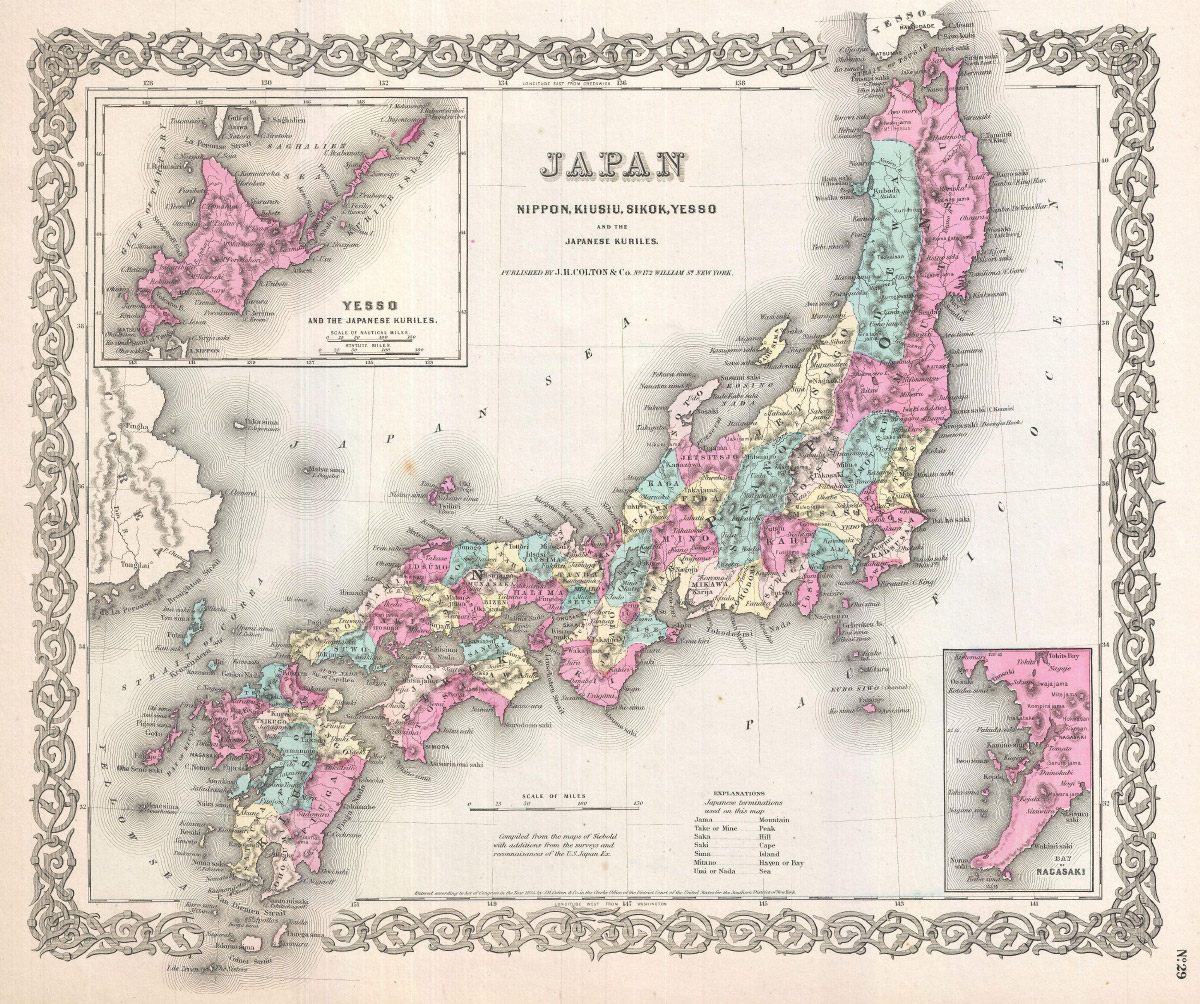

- Japan, Nippon, Kiusiu, Sikok, Yesso and the Japanese Kuriles. 1855. J. H. Colton, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. (Edo, now Tokyo, is written here as Yedo.)

- Map of Japan. Nations Online Project. (Current)

Text resources

- Trede, Melanie. Hiroshige: One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. Köln: Taschen, 2010. (This big, deluxe book with reproductions and great commentaries is available from both Multnomah County Library and PAM Crumpacker Library.)

- Smith, Henry D, and Amy G Poster, eds. One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. New York: George Braziller; Brooklyn Museum of Art, 2007.

- Guth, Christine. Art of Edo Japan: The Artist and the City, 1615-1868. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2014.

Spanish-language PDFs developed with the support and collaboration of