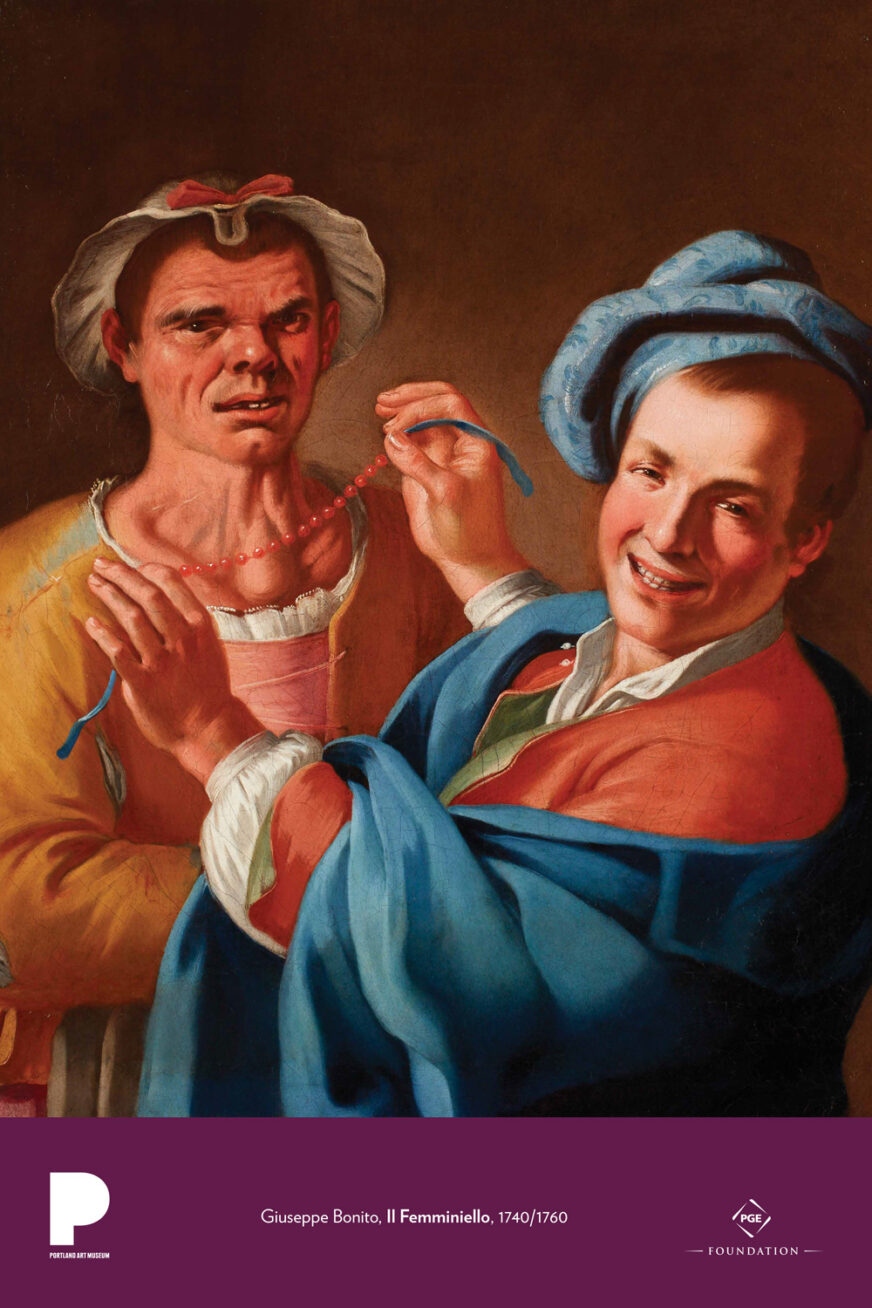

Owing to widespread social prejudice, cross-dressing was rarely depicted in European art until the modern era. This recently discovered painting from the mid-eighteenth century is a testament to the exceptional and long-standing acceptance of cross-dressers known as femminielli in the great Italian city of Naples. The term, which might be translated “little female-men,” is not derogatory, but rather an expression of endearment. Femminielli come from impoverished neighborhoods, as is evidenced by this individual’s missing tooth and goiter, a common condition among the poor in the Neapolitan region. Although femminielli cross-dress from an early age, they do not try to conceal their birth sex completely. Rather than being stigmatized, they are deemed special and are accepted as a “third sex” that combines the strengths of both males and females. In particular, femminielli are thought to bring good luck, so Neapolitans often take newborn babies to them to hold. Femminielli are also popular companions for an evening of gambling. This association is represented by the necklace of red coral, which is similarly thought to bring good fortune. Neapolitan genre paintings (images of everyday life) frequently feature a grinning figure to engage the viewer. Here, we are invited to consider the artist’s playful inversion of traditional views of gender, which contrasts the pretty young male with the more masculine femminiello.

In spite of Neapolitan acceptance, this painting is the only known representation of a femminiello before photographs made at the end of the nineteenth century. In keeping with Oregon’s leadership in LGBTQ rights, the Portland Art Museum prioritized acquiring this rare, early image of gender nonconformity at auction in 2014.

Giuseppe Bonito was an admired painter in eighteenth-century Naples, known for his portraits of the court of Charles III and his lively genre paintings depicting scenes of everyday life.

Discussion and activities

- Partner with another person and position yourselves as the figures in Bonito’s painting. How do you think each figure feels at this moment? What would each of these figures say? What happened right before this moment and what happens after this moment? Write a dialogue or a scene from a story or play.

- Many eighteenth-century paintings include one figure who invites the viewer into the scene. How does Bonito’s composition achieve this? As a contemporary viewer examining a historic work, what do you think of this approach? Does it feel authentic or staged?

- What role do inanimate objects, like clothes and jewelry, play in the painting? How do these objects contribute to the meaning of the scene?

- Consider Il Femminiello in its historic context—eighteenth-century Naples—and in the context of today. What can works from the past teach us about our own society’s views of gender nonconformity?

Recommended resources

- Dawson Carr, PhD, the Janet and Richard Geary Curator of European Art at the Portland Art Museum, discusses Bonito’s Il Femminiello in this lecture, “Gender Bending in 18th Century Naples,” delivered at the Portland Art in June 2016

- Nico Lang, “This 18th-Century Italian Painting Proves Gender Nonconformity Is Far From a Modern Invention,” Slate (July 11, 2016)