Crafted in southwest China during the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE), the Money Tree embodies wishes for eternal prosperity in the afterlife. As early as the fourth millennium BCE, the Chinese equipped tombs with utensils and provisions to help the deceased continue to prosper in the spirit world. The custom reached extremes during the early Bronze Age, when dynastic rulers were accompanied in death by human and animal sacrifices as well as vast amounts of precious bronze vessels and weapons. By the time of the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), a far more humane age, sculpted figures of clay or wood replaced human sacrifice as companions for the deceased, and inexpensive clay pots took the place of grain and wine containers made of luxury materials.

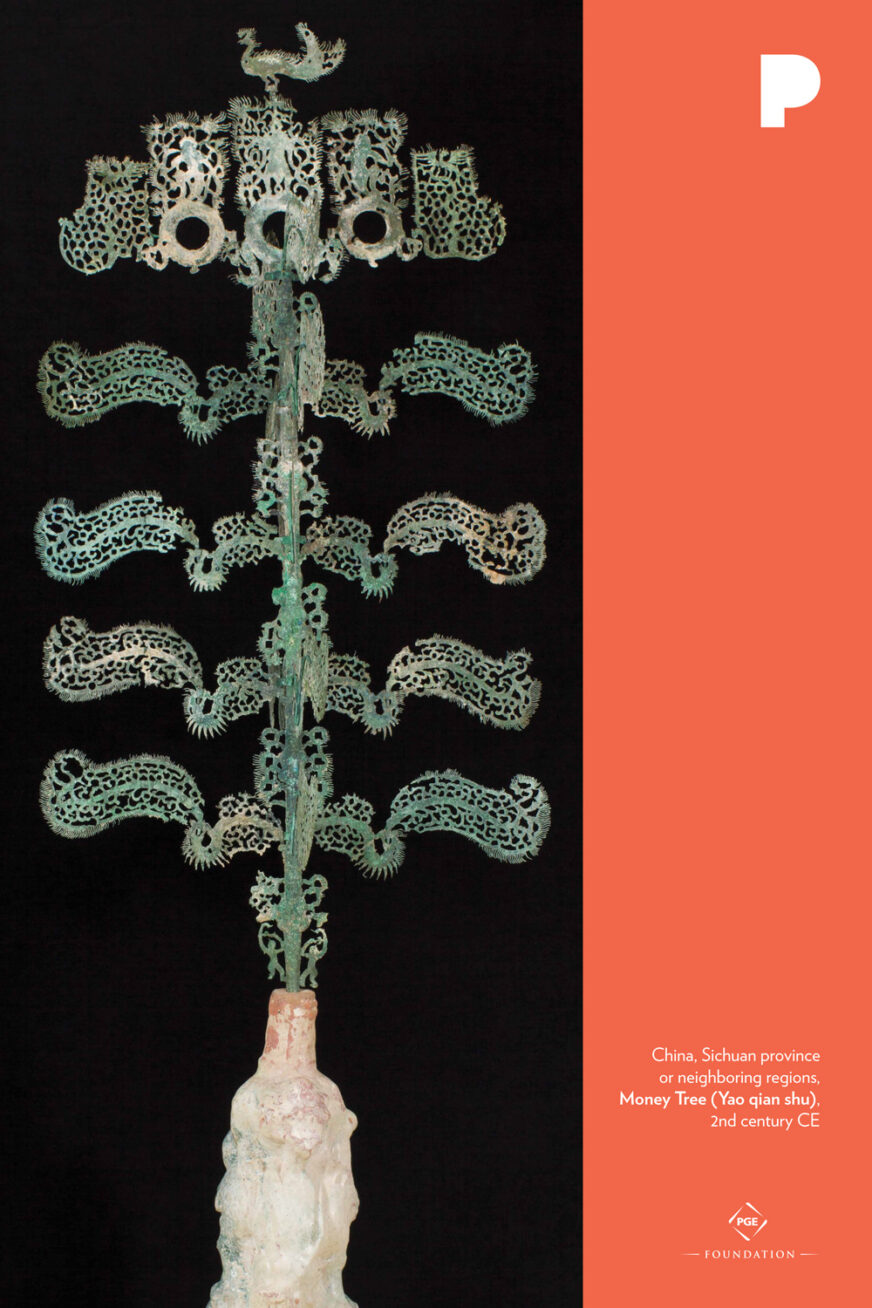

The Money Tree is an example of funerary art, an object made expressly for burial. Dragons and phoenixes, symbols of longevity, cavort across the surface of sixteen bronze leaves, each dotted with coin designs. (Wuzhu, a round coin with a square hole, was the most common currency of the day.) At the top of the tree sits a crested bird with a feathery tail. The bird is a clue that the tree itself is the magical fusang tree. According to legend, the gigantic fusang tree grows in the Eastern Sea. Every morning, the golden sun-bird perches on the tree, bringing light and warmth to the new day.

The crown of the tree features two monkeys holding bananas, flanking the figure of a man. Along the trunk of the tree are five small Buddha-like figures, each surrounded by an aura of coins that seem to radiate light. Each inner leaf of the tree portrays a dragon, coiled on its back. Each outer leaf culminates in the figure of a phoenix with its wings outspread, which appears to spew forth from the dragon. The elaborate shapes found in the Money Tree do not follow an established system. Rather, they represent a collection of auspicious figures who lend their blessings to their patron’s journey through the afterlife.

Money trees, such as this one, were made by casting molten bronze in a two-part mold. Casting served both practical and aesthetic ends, providing an even distribution of weight along the tree trunk and a harmonious design.

Based on research by Dr. Tami Lasseter Clare, Portland State University.

Discussion and activities

- Find the mythological creatures hidden in the Money Tree. What shapes do you notice on the trunk and leaves of this tree? What shapes do you notice at the top?

- What is the Money Tree made of? How do you think it was made? Was it shaped by hand or cast in a mold? Support your claims with specific observations about the work.

- What does this work tell you about Han culture and beliefs in the afterlife? Why do you think the patron commissioned this work to include in his or her tomb?

- Think about an object that has special meaning to you. What makes it significant? What does it represent?

- Of more than 70 money trees that have been discovered in southwestern China, only one was found intact. Most money trees, including this one at the Portland Art Museum, include some reconstructed parts. Dr. Tami Lasseter Clare and her students at Portland State University conducted a scientific study of the Portland Art Museum’s Money Tree to determine the date of each. Do you think ancient artifacts should be repaired, or do you think they should be left in the state in which they are found? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each approach?