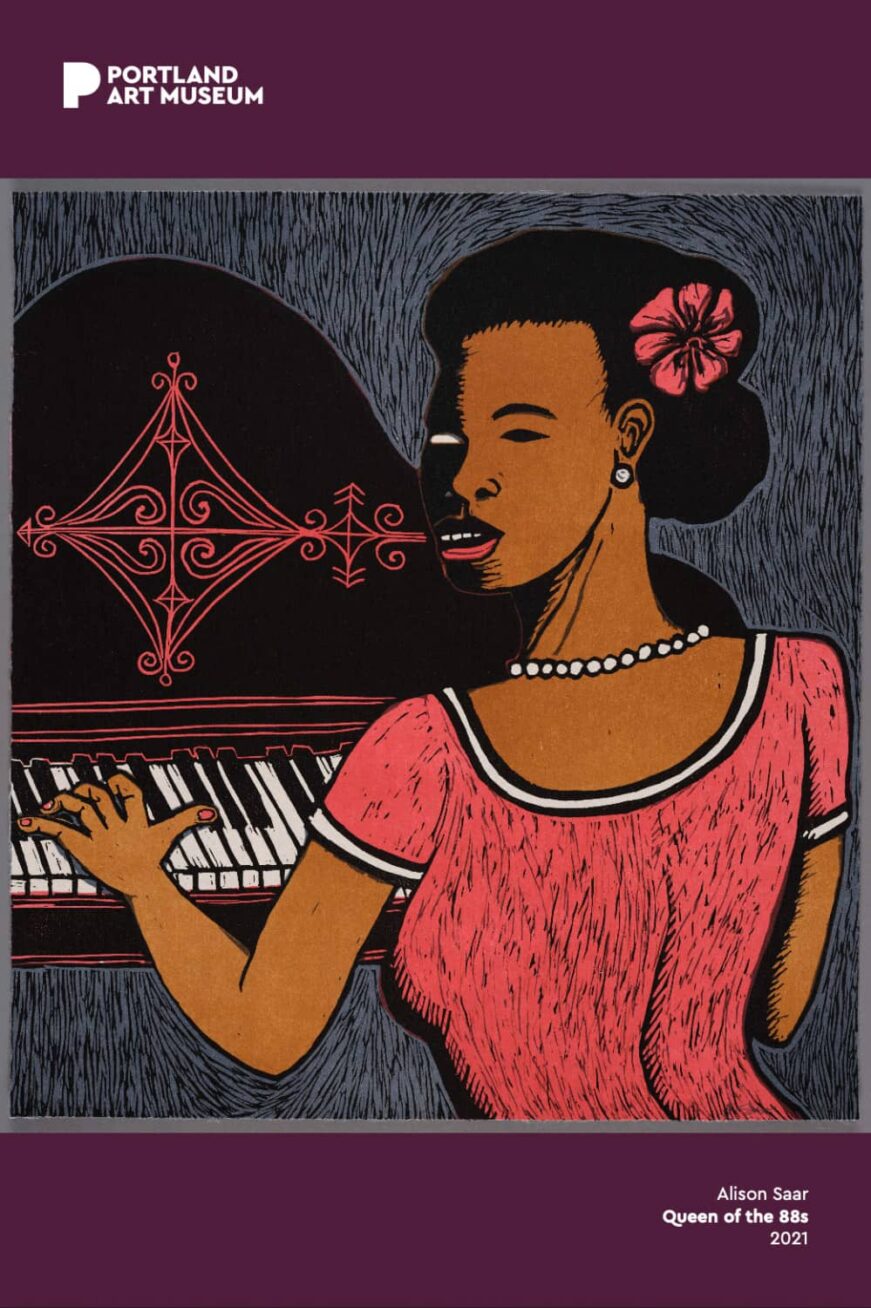

A brown-skinned woman looks over her shoulder at the viewer, acknowledging our presence. Her face is half in shadow, her body turned toward the piano before her. Her left hand stretches over an octave of the keyboard. Swirling, red lines extend against the flat black of the grand piano’s lifted lid, suggesting a music desk or, perhaps, her voice in song. The same red hue appears on her dress, nails, and the orchid in her hair. The arc of her back and the energetic black marks on her dress convey a sense of movement and rhythm. The piano seems to float in space as if the pianist could dance unencumbered while she played. She is indeed “Queen of the 88s”—the 88 keys on the piano keyboard.

In this lively image, contemporary artist Alison Saar pays homage to the Harlem Renaissance, the Black cultural and intellectual movement that flourished in the 1920s and ’30s. In the first decades of the twentieth century, hundreds of thousands of African American people fled Jim Crow laws and racial terror in the South and moved to cities across the North, Midwest, and West in what would come to be known as the Great Migration. The Harlem neighborhood in New York City became the center of a rich and varied Black cultural life. As a historian writes, “The Harlem Renaissance encompassed poetry and prose, painting and sculpture, jazz and swing, opera and dance. What united these diverse art forms was their realistic presentation of what it meant to be black in America, what writer Langston Hughes called an ‘expression of our individual dark-skinned selves.’”*

Saar lived in New York in the 1980s, including a year as artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem. In a series of prints, including this one, she draws attention to the prominent role of music in Harlem culture. The Queen of the 88s inhabits a community of dancers, musicians, and singers who populate Saar’s brightly colored sheets.

Alison Saar’s artwork consistently focuses on the African diaspora and Black female identity. But she may be better known as a sculptor, mixed-media, and installation artist than printmaker. Born in Los Angeles, Saar was raised in a family of artists: the daughter of acclaimed collagist and assemblage artist Betye Saar and ceramist and art conservator Richard Saar. As a teenager and young adult, Saar worked with her father and developed a deep understanding of materials. Her appreciation of texture carries over to her linocut prints as we see in Saar’s strong, energetic mark-making.

Printmaking offered new expressive possibilities to an artist who sees herself as fundamentally “a storyteller”: “Making a 2-D work meant I could introduce all these other things that couldn’t be part of a sculpture. I could have smoke, or ghostly figures lurking about. Sculptures are solitary objects often contextualized by the space they inhabit. Here, I could dictate that context, create a scene, a tableau, a narrative.”** We see all of these effects in the series of 10 prints Saar created while in residence at Mullowney Printing in Portland in 2019, eight of which comprise the suite Copacetic. Taken together, the prints conjure a vivid world of Harlem nightclubs, peopled with exuberant jitterbug dancers, drummers and saxophone players, moody couples clutching their cocktails, and even a few ghosts.

Discussion and activities

- Write a story inspired by Queen of the 88s. Consider including other works from the Copacetic series. Who are the characters? What happens just before this moment and what happens afterwards? As an extension, read and discuss poetry and fiction by Harlem Renaissance writers, such as Langston Hughes and Nella Larsen.

- How does Alison Saar convey the energy and feel of jazz music in this print? Consider her use of color, line, and marks. Listen to jazz recordings from the Harlem Renaissance, such as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, and Hazel Scott. What images, colors, and shapes come to your mind? Create a work of art in response to this music.

- Alison Saar always leaves the eyes blank in the faces of the people she depicts. She associates the blank eyes with African masks and, also, a kind of protection and dignity for the figures who can’t be fully known by the viewer. How do you respond to the blank eyes of the figure portrayed in Queen of the 88s? Experiment with creating a representation of a figure in which you leave some parts blank. For example, you might draw a portrait, then erase or conceal some elements of the face or body. What is the effect of the blank space?

* “A New African American Identity: The Harlem Renaissance,” Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, accessed December 15, 2025, nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/new-african-american-identity-harlem-renaissance.

** Alison Saar, “Fighting Flatness” in Mirror, Mirror: The Prints of Alison Saar from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation. New York: Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation, 2019.

Selected sources

Mullowney Printing: Alison Saar and Collection: Alison Saar: Copacetic.

Alison Saar. National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Hadley Roach, “Thread to the Word: Alison Saar,” BOMB, November 17, 2011.

Sayaka Matsuoka, “Themes of race and identity reflected in artist Alison Saar’s new Weatherspoon show,” Triad City Beat, Nov. 14, 2019.

Alison Saar: Bound for Glory. Sept 7 – Dec. 12 2010. Hoffman Gallery, Lewis and Clark College.

A New African American Identity: The Harlem Renaissance, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

E. Simms Campbell, Cartographer and Publisher. “Night-club Map of Harlem” in Manhattan Weekly for Wakeful New Yorkers. 1932. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

Great Piano of Hazel Scott. YouTube. 2:22.