In classical Indian culture, dance is a demanding physical discipline. Dance prepares the mind for spiritual leaps: the dancer enters a trance, the dancer and the dance become one, reenacting the union of the individual soul with the transcendent divine.

The great Hindu god Shiva has many aspects or forms. Here he appears as Natarāja, the Lord of the Dance. The dance illustrates Shiva’s role as the deity who destroys the cosmos so that it can be renewed again. Shiva oversees the endless cycles of time, marking its pace with his drum and footsteps.

In about the mid-tenth century, the rulers of the Chola dynasty in South India chose Natarāja as their clan deity. As a result, artists made many sculptures of Natarāja. Some were made of granite. Others, like this one, were made of cast metal and reserved for sacred processions. Long poles would have been inserted into the holes in the lotus-petal base, so that worshipers could carry the sculpture—draped in silk garments and garlands of flowers—through the streets on festival days.

Let’s look closely at this sculpture.

- Shiva stands within a circle. Long ago, small sculpted flames would have been placed around the edge of the circle, but these were lost to damage. If complete, the circle of fire suggests the flame that consumes all in the destruction at the end of an era. You can still see incised swirl patterns on the circle, suggesting the movement of flames.

- Shiva has long, matted locks of hair. At the top of his head, these have been piled up in a spreading fan shape, which then connects to the circle of flame. To the side of Shiva’s head, more locks of hair fan out to the side, filled with small flowers. The Goddess Ganga is enmeshed in Shiva’s hair. (She had been taken captive by the Moon, and Shiva saved her when she fell to earth by allowing her to land in his matted hair.) Shiva’s wild hair suggests the frenzy of his dance.

- Shiva has four arms! Many Hindu deities are represented in art with multiple arms, legs, or even heads, as a way to indicate that they have superhuman powers. In Shiva’s upper right hand, he holds a small drum, known as a damaru, with which he beats out the rhythm of his dance. In his upper left hand he holds a small flame, signifying the powers of both destruction and creation. He holds his lower right hand with the palm up, in a gesture of reassurance. Shiva’s lower left hand points down toward his foot, calling our attention to the fact that he is trampling a demon.

- The demon lying under Shiva’s foot represents ignorance and evil.

- Shiva wears a short dhoti—a sort of close-fitting kilt—as well as quite a bit of jewelry. A cobra, a symbol of Shiva’s yogic power, wraps around his torso.

An ancient Chola poem describes the symbolism of Natarāja this way:

The sound of his sacred drum awakens the cosmos into being;

his uplifted hand of hope sustains and protects it;

with his purifying fire, ego is destroyed;

his foot planted on the ground is an abode of rest for the tired soul, caught in the binds of illusion;

and his lifted foot promises release.

Pronunciation guide:

Shiva Natarāja = SHEE vah Nah tah RAH zha (Sanskrit)

Chola = CHO lah

Discussion and activities

- Look closely at the sculpture. Compare photographs of the sculpture from different angles, available online and on the back of the poster. What do you notice about this figure? What can you identify? What do you see that suggests dance? What do you see that suggests destruction and creation?

- Let’s try to get a sense of what it feels like to be this form of Shiva. Start by warming up.

- Stand with space around you.

- Roll shoulders—backwards, forwards, backwards. Swing arms, move from waist.

- Begin with top of your head and roll down, vertebra by vertebra, until you touch your toes, shins, or knees. Roll back up.

- Plant feet hip distance. Without moving your feet or falling over, shift your weight: forward, backward, right side, left side. One circle clockwise, one counterclockwise.

- Now, pose as Shiva. Lift one leg. Position arms—you choose which two arms.

- Indian sculpture tells us about the character or personality of deities and saints through the use of symbolism—something it has in common with the religious imagery of Christianity and Buddhism. (Not all religions communicate visually this way, however. Islam is an important exception.) For example, the drum seen here is associated with the rhythm of Shiva’s dance, and the demon underfoot symbolizes the ignorance and evil that the dance liberates us from. For a symbol to be effective, it has to be recognized and understood by many people. Can you think of symbols that you see in your daily life (for example, school mascots or brand logos)? Choose one symbol to analyze. What does this symbol communicate? Would its meaning be accessible to someone from another culture or country or religion? Why or why not?

- This figure was made to be carried in a procession through the streets of a city, where it would have been seen by hundreds of people. Compare that experience to your own experience with the sculpture at the Portland Art Museum or on this poster at your school. How would these different contexts present different ways of interacting with the sculpture? How would these different contexts affect the meaning of the sculpture?

Additional resources

- Prepared by Maribeth Graybill, PhD, The Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Curator of Asian Art

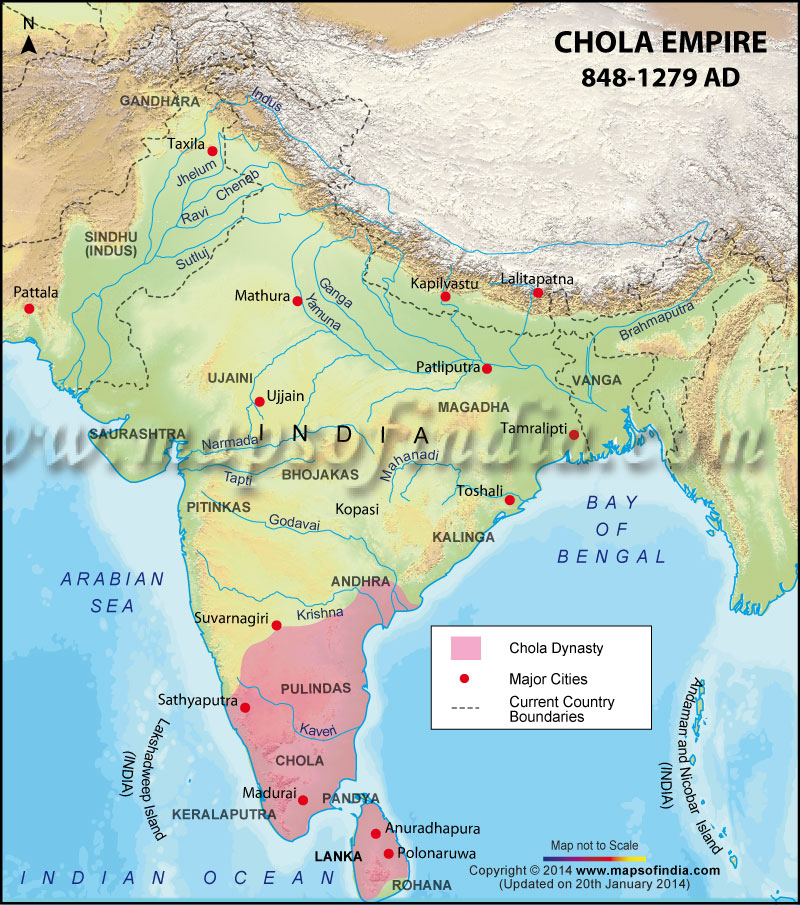

- Chola Dynasty

- The modern country of India has a long history of civilization. Many different kingdoms competed for rule over the centuries. The Chola was one of the most successful in terms of longevity; prosperity; high levels of cultural accomplishment in architecture, art, and literature; and influence on surrounding regions. The dynasty was founded in the third century BCE, but most of our knowledge about it comes from its era of greatest dominance, from the mid-ninth to late-thirteenth centuries. Through trade relations, the Chola also exerted great influence over neighboring cultures along the eastern coast of India and what is today Thailand and Indonesia.

Spanish-language PDFs developed with the support and collaboration of

Lost wax casting

Documentary On Sculpture Making – Moving Art | Pocket Films

In brief:

- The figure of an idol is carved in a wax (beeswax) that has been mixed with other materials to the desired shape.

- Clay is packed around the wax model.

- The clay mold is heated in open fire to melt the wax, which flows out; and then molten copper alloy is poured into the mold.

Although many sources refer to South Indian cast metal sculptures as “bronzes,” technically the material is not bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), but an alloy of copper with several other metals. The lost wax process is fundamentally the same technique used in most parts of the world, including by the great French sculptor Auguste Rodin.

Background: Indian Concepts of Time

All of the world religions that have arisen in India, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, begin with the concept that time is cyclical, rather than directed toward a particular goal, as in Christianity. A natural corollary of this is that human souls also pass through cycles of death and rebirth. Indian religions recognize and affirm the value of each stage of human life: learning (childhood through youth), householder (married life, caring for one’s parents and children, working), and old age (when one can turn to taking care of one’s own spiritual needs). The goal of the religious life is to find release from this endless cycle of rebirth. There are many paths toward that goal, including:

- Meditation and yogic practices to control the body. Shiva is considered the ultimate yogin.

- Devotion to a deity, seeking the deity’s assistance in everyday affairs as well as a sort of mystic union. Bhakti is the name for various devotional movements in Hinduism.

- Good deeds, including acting in accordance with one’s place in life (rulers, for example, are expected to administer their territories justly); making offerings to temples and monastic/priestly communities; commissioning religious images, sacred texts, or temples; compassionate acts such as building hospitals, feeding the impoverished, and so forth

- Seeking the intercession of priests

Processional Images

Copper alloy images were not the icons that Hindu devotees would have seen on visiting the temple: the main temple icons in Chola temples were usually massive figures carved from granite. The cast metal images such as the Portland Art Museum sculpture were reserved for use in sacred processions; otherwise, they were kept in a special storeroom on the grounds of a Hindu temple. One temple might have many similar images, perhaps dedicated and donated by different people. In the royal family, it might be successive generations; in a village temple, it might be different landowners or guilds who donated an icon, and so on.

In their original context, almost no one would have seen the Shiva Nataraja as we do today in the Museum. When taken out for a procession, the image would have been adorned in many layers of colorful silk and garlands of flowers, as tokens of respect for its sacred nature.

The interesting question is, then, why did Chola culture develop and expend such extravagant wealth to create processional images? (Copper was a costly material and craftsmen who specialized in making icons required years of training.) Why take icons out on parade? The answer lies in the Indian concept of darshan: to see a deity (or a revered person or sacred object)—and to be seen by a deity—is a powerful blessing. Only a few priests were allowed into the sacred spaces of a temple, but the entire population could gather to see the sacred icons when they were paraded through the city.

Recommended resources

- The Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC

- Diana Eck, Darsan: Seeing the Divine Image in India, 3rd ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988).

- The most famous monograph on the iconography of Shiva Natarāja is by Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy, The Dance of Siva (1918).

- The Wikipedia article on Shiva Natarāja is excellent.

- A good book for children is Sanjay Patel, The Little Book of Hindu Deities: From the Goddess of Wealth to the Sacred Cow (New York: Penguin, 2006).