In Japanese culture, poetry and painting have been sister arts since ancient times: paintings were often based on poetic topics, and poems were composed about paintings. The eighteenth-century artist Yosa Buson is celebrated both as one of the greatest haiku poets of all time and as an exceptional painter. In both art forms, he focused on conveying a fleeting sensation—a momentary emotion or perception distilled to its essence—often connecting human experience and the natural world.

Buson’s first art was poetry. Born to a family of farmers in a village outside Osaka, he moved to the metropolis of Edo (present-day Tokyo) at the age of 20 to become a disciple of the haiku poet Hayano Hajin (1676–1742). After Hajin’s death, Buson spent nine years travelling through northern Japan, retracing the steps of the revered seventeenth-century haiku poet Matsuo Basho (1644–1694). Buson would eventually be credited, along with Basho, with developing haiku into a major literary art form. Consisting of just seventeen syllables, in lines of five, seven, and five syllables, these short poems use concise, sensory language to convey a feeling or image.

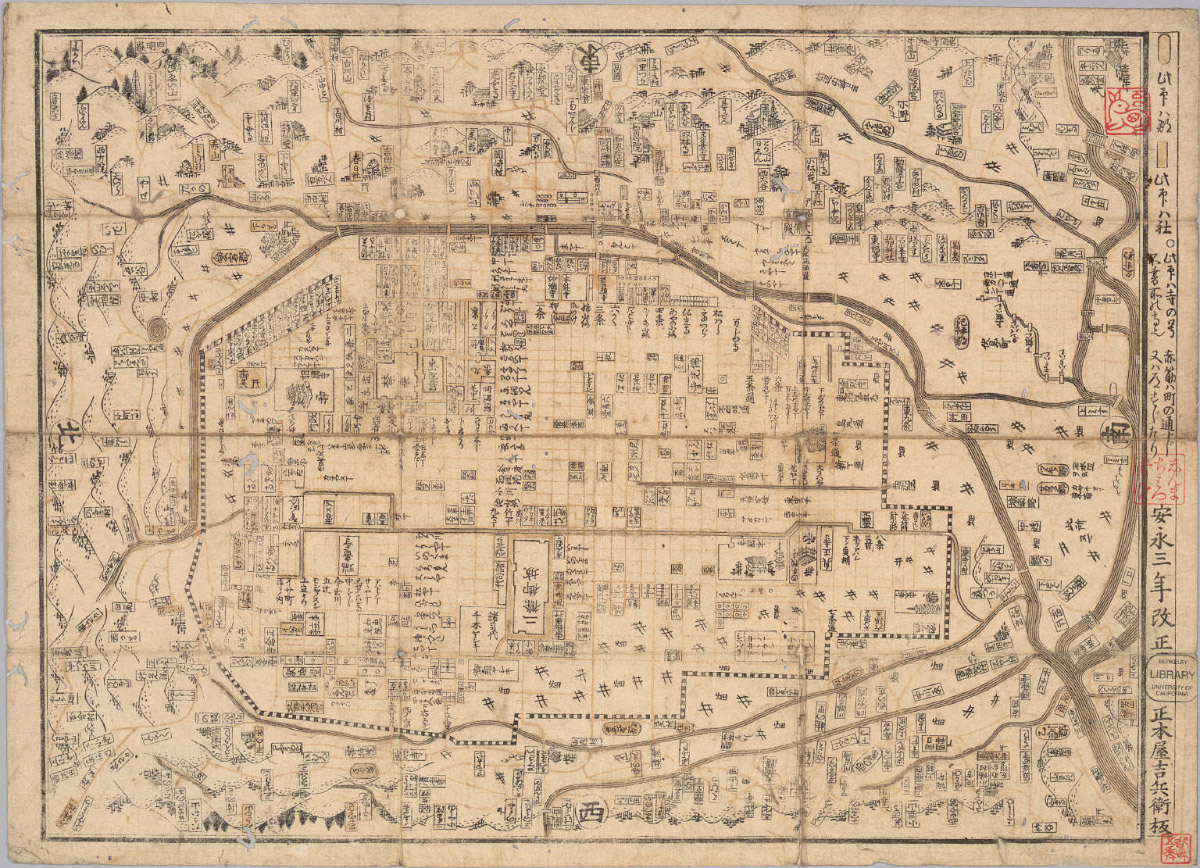

In the late 1750s, Buson moved to Kyoto, historically the cultural center of Japan as the residence of the emperor. He built a loyal following of his own poetry disciples but, reluctant to earn money from poetry, he focused on painting as a source of income. He became increasingly interested in Chinese painting styles, then accessible primarily through printed books, and experimented with various modes. His technique improved rapidly, and by the late 1760s he had become a leading artist in the newly emerging genre of literati painting.

Unlike traditional schools of painting in Japan, which were based on apprenticeship training within a family and often entailed a distinctive stylistic “brand,” literati painting can be described as an attitude toward the act of making pictures. Inspired by Chinese precedents, literati painting is an art form that emphasizes self-expression and calligraphic brushwork. In Japan, it was taken up within a broad framework of shared appreciation of Chinese poetry, philosophy, and pictorial models. For Buson and his contemporaries, Chinese was ingrained from childhood as their primary written language; Chinese texts had long been available in manuscript and printed form. Chinese literati paintings were still rare in Japanese collections, so access to visual models came mainly through imported printed books. A few Chinese painters who spent time in Nagasaki, the sole Japanese port open to foreigners at the time, were another important source of information.

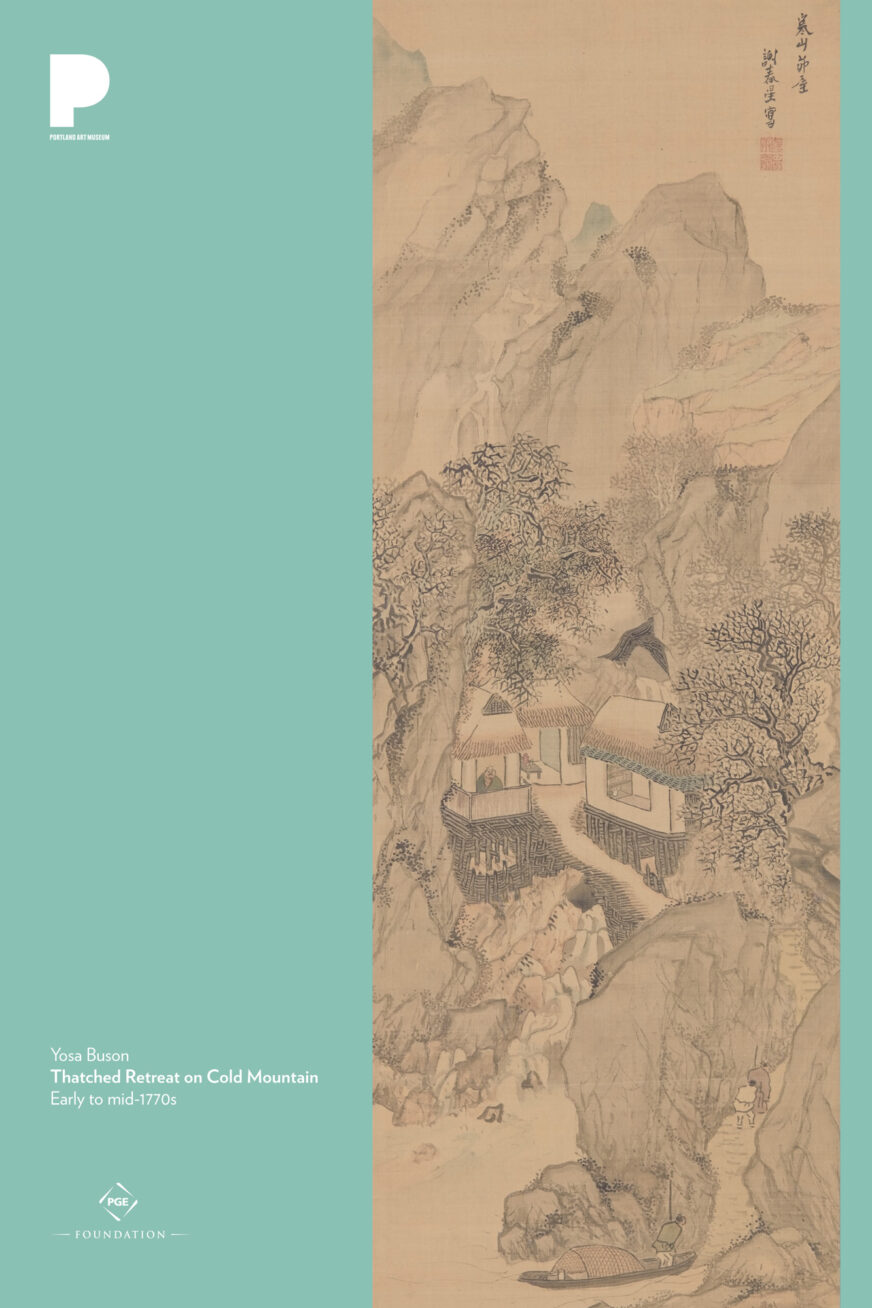

Thatched Retreat on Cold Mountain can be seen as Buson’s commentary on one of the key themes in Chinese literati painting: the ideal of seclusion. In traditional China, the main path to wealth and prestige was through government service, but too often that required moral compromise. To resign or attempt reform from within was a perennial dilemma, and retreat to a secluded hut in the mountains was always seen as the more noble choice— in literature if not in actual practice. For those who could not escape their mundane responsibilities, landscapes offered a virtual form of escape.

In Buson’s painting, a scholar sits by a window in a tiny thatched cottage that is perched on stilts over a rushing mountain stream. One can almost hear the water, tumbling over rocks on its way to the river below, the sounds made even louder as they echo among the bare trees in the narrow canyon. In an adjacent room, tea is already set out for the friend who has just arrived and is working his way up the steep path. For a recluse, visits from friends offer a welcome break from solitude. But there is a double layer of meaning in this painting, for the scholar’s gaze is directed at us: we ourselves are invited into Buson’s private world, to share the pleasure of friendship.

The calligraphy in the upper right of the painting is the title of the work and Buson’s signature, in which he uses one of many pseudonyms. The seals are also those of the artist. Although the work is not dated, on a stylistic basis it may be assigned to the early to mid-1770s, when he was in his late fifties and entering his most prolific period. By common acclamation, his greatest works are those produced between about 1770 and his death in 1783.

This work is a hanging scroll, a format of painting traditionally displayed in an alcove in the most formal space in a Japanese home. Hanging scrolls are not meant to be on permanent display, but instead brought out on special occasions, such as a seasonal festival or to honor a guest. When not on view, the scrolls are rolled up and stored in custom wooden boxes, keeping them safe from moisture and insects.

As a poet, Buson sought to “use the commonplace and transcend the worldly.” The following verses are from Collected Haiku of Yosa Buson, translated by W.S. Merwin and Takako Lento (Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press, 2013), 204 and 216.

In the wild winter wind

the voice of the water cracks

falling across the rocksIn a grove of winter trees

I look at the moon and forget

misery everywhere

Note on the artist’s name: In Japanese names, the family name precedes the given name. In Buson’s case, as with many other artists of his era, both names are pseudonyms adopted by the artist to reflect some aspect of his character. Buson, which means “turnip village,” was the name he used as a haiku poet; he rarely used it as a signature on his paintings. The pseudonyms he used as an artist changed over the years, but included Shunsei (Spring Star), seen here, and Sha’in.

Discussion and activities

- Consider this image in relation to one or more of Buson’s poems. What connections do you see between his writing and his painting? How does he communicate specific sensations and moments in the image and in words?

- Collaborative poem activity: Ask a group of students to study the image silently for up to three minutes. Then, invite them to call out words—popcorn style—that describe the image. Divide the students into small groups of about three people. Ask each group to create a haiku. Read the poems aloud to each other.

- Compare Buson’s painting to landscapes by European or U.S. artists, such as Albrecht Dürer’s The Monstrous Sow of Lanser (1496) or Charles Heaney’s Mountains (1938), included in the Poster Project. Notice how your eye moves through each of the scenes. What differences do you notice in your perspective as a viewer? How do you orient yourself? What is the effect of the presence or absence of a horizon line?

- Look closely at the brushstrokes that Buson uses in the painting. How many different types of brushstroke can you identify? How do they work together to create the scene? How do they relate to the calligraphy in the upper right corner? Experiment with these brushstrokes yourself. Use a viewfinder, such as an empty slide frame or rolled paper, to focus on a small part of the image and copy it with your own paint and brushes.

Sources

Print Resources

- Yosa, Buson. Collected Haiku of Yosa Buson. Translated by W.S. Merwin and Takako

- Murase, Miyeko., Burke, Mary Griggs, and Metropolitan Museum of Art. Bridge of Dreams : The Mary Griggs Burke Collection of Japanese Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art : Distributed by H.N. Abrams, 2000.

- French, C., University of Michigan. Museum of Art, & Asia House Gallery. (1974). The poet-painters, Buson and his followers : An exhibition, the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, January 9-February 17, 1974 ; the Seattle Art Museum, Washington, March 28-May 12, 1974 ; the Asia House Gallery, New York, October 3-December 1, 1974. Ann Arbor]: University of Michigan Museum of Art.

- Cahill, James, Asia House Gallery, and University of California, Berkeley. University Art Museum. Scholar Painters of Japan : The Nanga School. New York: Asia Society; Distributed by New York Graphic Society, 1972.

Web Resources

- “The World of Brush and Ink” – Arata Shimao, Poetic Imagination in Japanese Art Symposium Lecture (2018)

- “This is not a Pipe!”: The Relation of Artistic Identity and Patterns of Abstraction in Representation in Literati Painting– Paul Berry, Poetic Imagination in Japanese Art Symposium Lecture (2018)

- List of educator resources on Asian art from the University of Oregon

- Educator resources on Asian art history from the Smithsonian

Spanish-language PDFs developed with the support and collaboration of