Hundreds of millions of studio portraits and everyday snapshots were made in the United States during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Although commonplace, these vernacular pictures demonstrate photography’s significant role in shaping personal and collective identity. For African Americans, photography offered an especially important tool of self-representation and opportunity to resist the racist and stereotypical images produced in dominant U.S. culture.

In the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, as photography grew into a widely accessible and affordable form of self-representation, African Americans struggled to establish selfhood in a country largely founded on their forced labor. Picture postcards depicting lynchings, cotton pickers, chain gangs, and “alligator bait” were produced and distributed throughout the world. But personal cameras provided African Americans a means to challenge these racist depictions. In the words of cultural critic Bell Hooks, the camera offered African Americans “a way to empower ourselves through representation.”

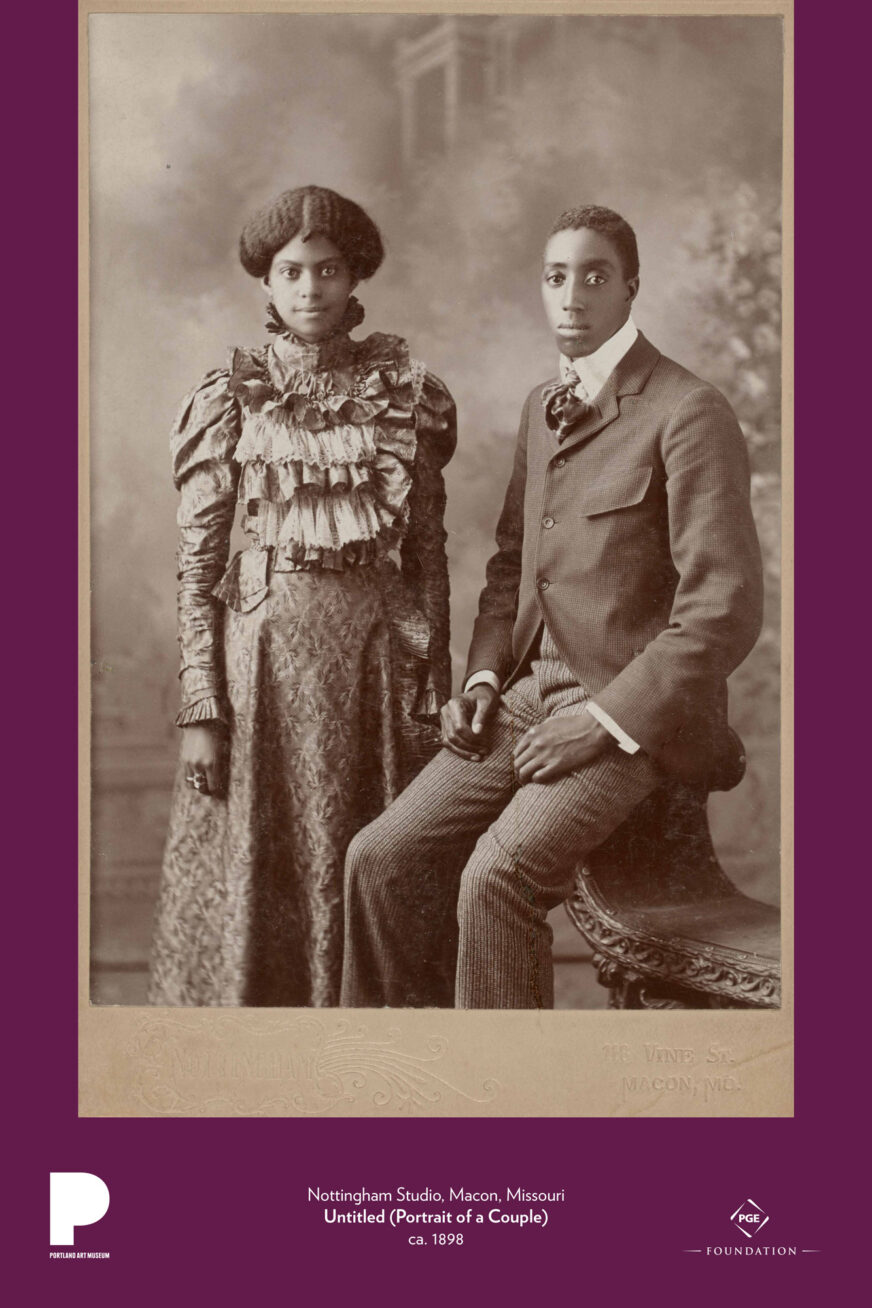

The photograph reproduced here is now considered anonymous: we do not know the identities of the makers or their subjects. But these people were not nameless when the picture was taken. Migration and displacement, among other factors, contributed to the disappearance of this knowledge. Although the photograph’s anonymity symbolizes loss, the portrait simultaneously conveys resistance in the face of systemic inequality and the power of shaping self-identity through the camera’s lens.

Images such as this one offer a reminder that there is a long history of people choosing to represent themselves through photographs. Photography first became available to the public in 1839, but was expensive in its earliest forms. Over time, competing inventors and advances in optics and chemistry reduced costs, making photographs increasingly affordable for the working and middle classes. Giving and collecting portraits became a popular pastime in the late nineteenth century, paving the way for Kodak camera snapshots in the early twentieth century and instant Polaroid pictures after World War II. Most digital images go unprinted today, but sharing of selfies via text, email, and social media demonstrates the continued importance of self-fashioning through photography.

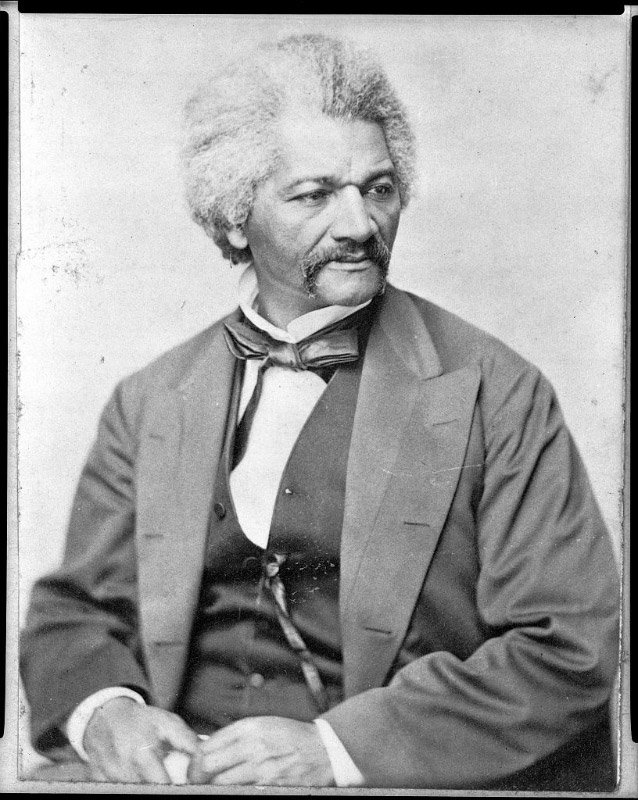

In the nineteenth century, prominent abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass believed that the new medium of photography was the ideal instrument to establish and strengthen African American identity. In essays and public speeches, he argued that “the humblest servant girl may now possess a picture of herself such as the wealth of kings could not purchase fifty years ago,” asserting that such portraits “highlighted the essential humanity of [their] subjects.” Douglass’ conviction that photography could be a tool for civil rights was so strong that he posed for at least 160 portraits between the early 1840s and his death in 1895. The most photographed American of the nineteenth century, he sat for more portraits than Abraham Lincoln.

The studio portrait shown here was created in Macon, Missouri, and comes from the family album of Carl and Mercedes Deiz. Carl, a lifelong Portland resident, was a Tuskegee Airman during World War II. Mercedes, originally from New York City, was the first black woman to be admitted to the Oregon State Bar and serve as a district court judge in the state. Mercedes’ parents and Carl’s father had immigrated to the United States from the Caribbean and Eastern Europe. Carl’s mother, Elnora “Nonie” Foster Deiz, and grandmother, Mollie Sanders Foster, were born and raised in the Midwest. Mollie brought the album, containing pictures made in Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, Colorado, and Tennessee, with her when she moved to Oregon with her husband and daughter in 1918. Mollie’s photo album was the inspiration for the 2017 Portland Art Museum exhibition Representing: Vernacular Photographs of, by, and for African Americans.

Members of the Deiz family continue to live in North Portland. We are grateful that they chose to share their family legacy with the community through the Portland Art Museum.

Discussion and activities

- Look closely at the portrait. Write 10 words describing the people represented here. What do you notice about their posture, their clothes and hairstyles, their facial expressions? How do they interact with the camera? What do you think they wanted to convey about themselves through this portrait? Who do you think is the intended audience or viewer?

- What family photos do you have that mean a lot to you? Why? What would you want us to know about you and your family based on the images you select?

- Imagine that you are having your portrait made by a professional photographer in a studio. You know that the portrait will be saved and passed down to future generations. How would you choose to present yourself? Consider your clothes, jewelry, hairstyle, position, whether you would be alone or with others, any scenery or furniture.

- A vernacular photograph is a picture that captures an everyday subject. School portraits, selfies, vacation snapshots and postcards, photobooth pictures, government identification photos, and formal wedding portraits are all considered vernacular. In the past, art museums did not display these sorts of photographs. But, in recent years, museum professionals have increasingly recognized the artistic and cultural value of vernacular works. What is the significance of exhibiting vernacular photographs in a museum? What does it mean to display photographs like this one—intended for living room walls or family photo albums—in a public space like a museum?

Recommended resources

- Representing: Vernacular Photographs of, by, and for African Americans in Portland Art Museum online collections. 119 photographs.

- Representing Timeline and Family Tree

Spanish-language PDFs developed with the support and collaboration of

- Understanding the wet collodion process. Khan Academy and the J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Deborah Willis, ed., Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography (New York: New Press, 1994).