Overview

One of the Museum’s most cherished and beloved paintings, Claude Monet’s Waterlilies (1914-15), is receiving a long-awaited conservation treatment. Conservation will focus on removing a non-original synthetic resin varnish to return the painting more closely to Monet’s intended appearance. We invite you to learn more about this wonderful painting and to follow along on its conservation journey.

The restoration and related programs are supported in part by a generous grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project.

Waterlilies

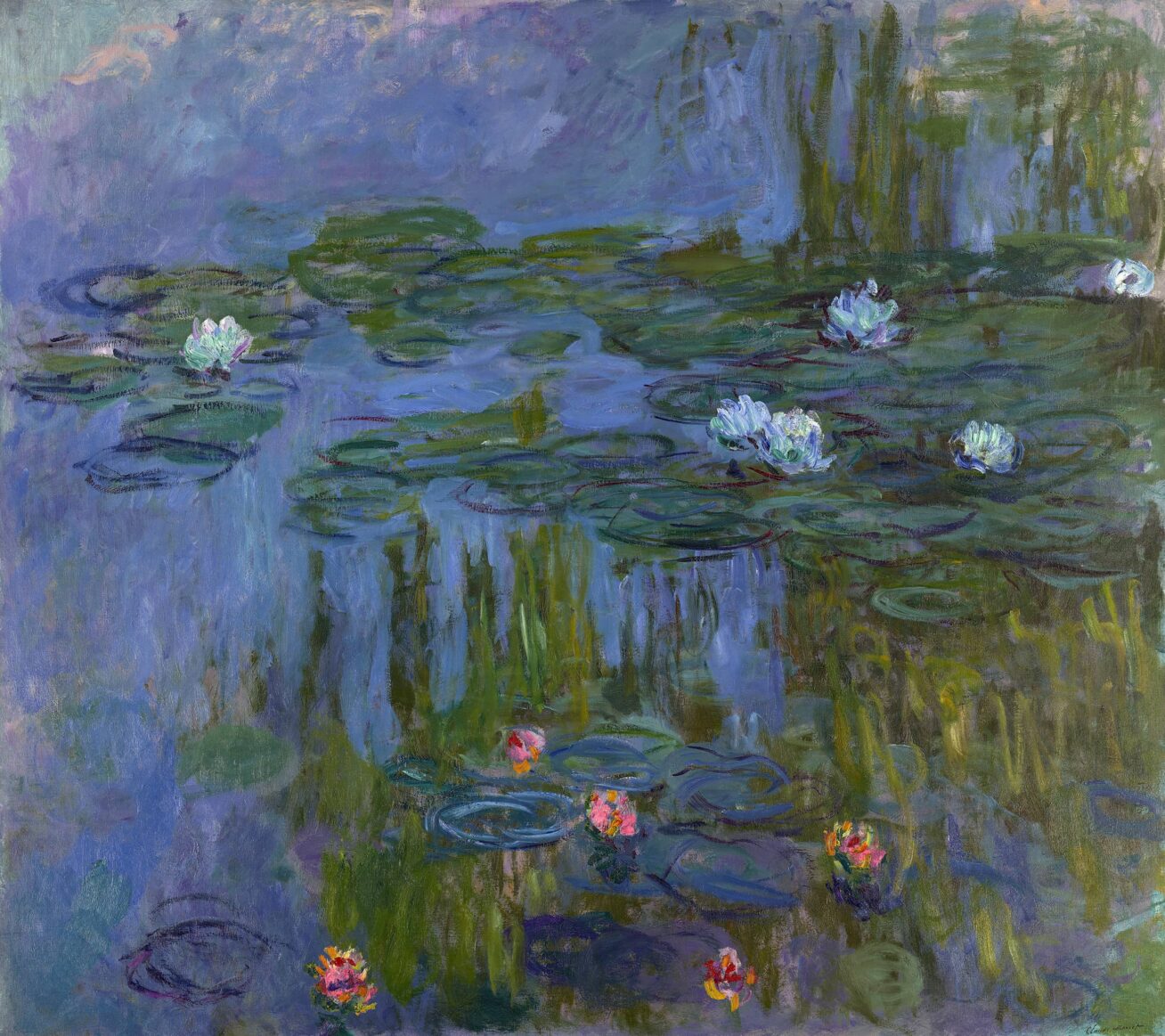

Waterlilies was painted between 1914 and 1915. Monet was seventy-six years old and had only recently returned to painting after a long hiatus following the death of his beloved wife, Alice. Although in this artwork he returns to a theme he had painted before—his waterlily pond—it is with a new focus and approach. Monet revisits an idea he had been mulling over for some time, of creating a Grandes Décorations—paintings on a grand scale that would envelop the viewer—as his gift to France. In Waterlilies we see Monet beginning to work out these ideas. The canvas is larger, no longer easel-size, the brushwork is freer, and his approach is increasingly abstract. There is no longer any reference to the shore or the horizon; instead, the focus of the painting is the ever-changing light, shadows, and reflections. Monet speaks often of seeking to capture that which exists between himself and his subjects:

For me, a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment; but the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life—the light and the air which vary continually. For me, it is only the surrounding atmosphere which gives subjects their true value.

Conservation strategy

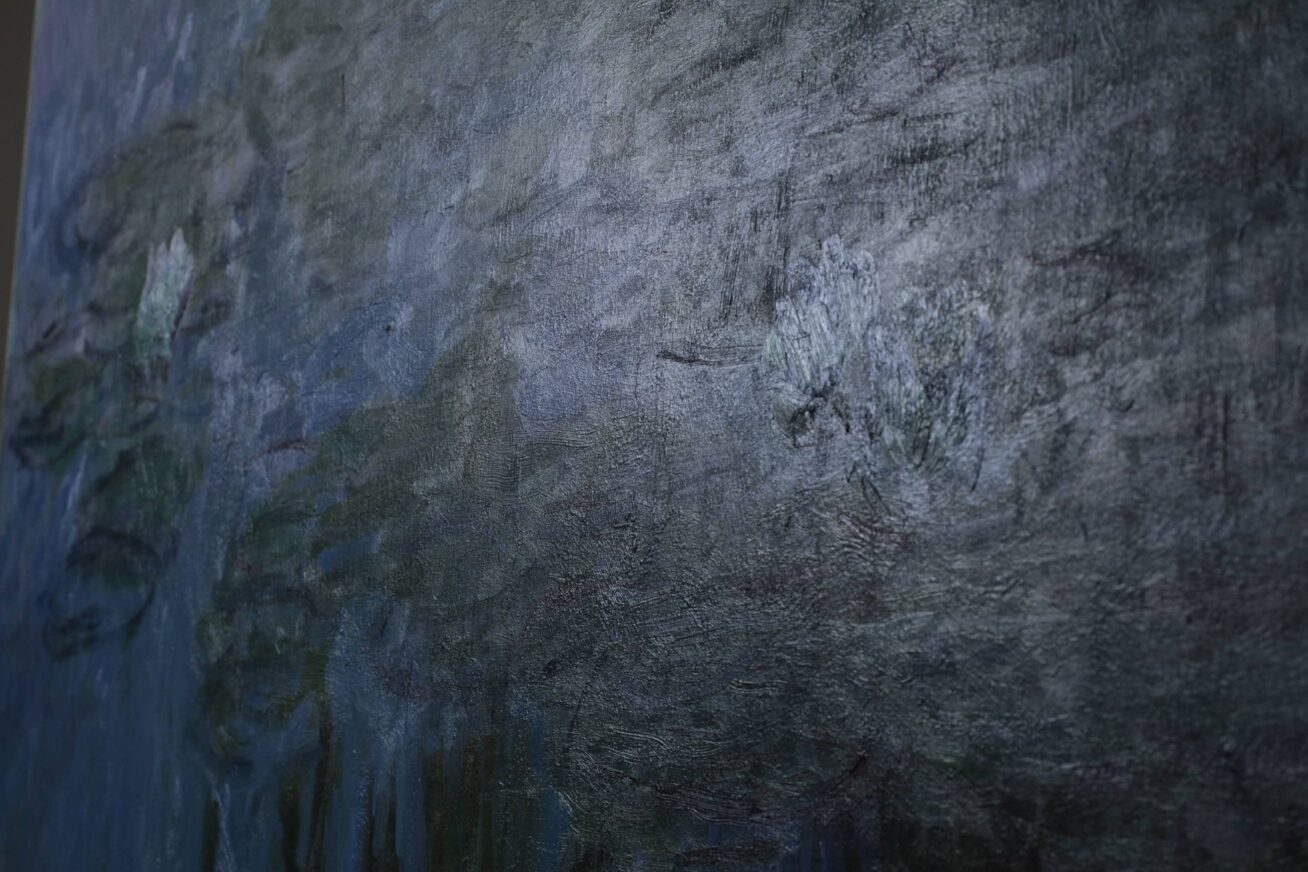

Waterlilies is undergoing conservation treatment to remove an acrylic resin varnish applied in 1959. The aim is to return the painting more closely to the intended appearance.

Beginning in the 1870s, Claude Monet made it clear that his paintings were not to be varnished, as did many other Impressionists regarding their works. He speaks often of seeking to capture that which exists between himself and his subjects: the air, the “ether,” the atmosphere. A critical aspect of portraying this intangible quality is a very intentional emphasis on the painting’s surface. Monet sought a textured, matte, and chalky surface with subtle variations of luminosity and tone.

The varnish applied to Waterlilies substantially alters these essential soft, delicate tonalities. It saturates the paint films, distorting the colors and altering their intended relationship to one another.

This saturation affects both the value (lightness or darkness) and the intensity (brightness or dullness) of the colors. Pigments change in different ways through increased saturation. This change is especially pronounced in blue pigments, which become much darker.

In addition, the varnish imparts an overall glossiness that reflects light differently than a matte paint film would, masking any variations of gloss and matte that exist within the paint films themselves. The removal of this inappropriate varnish will improve the overall appearance of the painting and restore Monet’s intended emphasis on its surface.

Painting en plein air

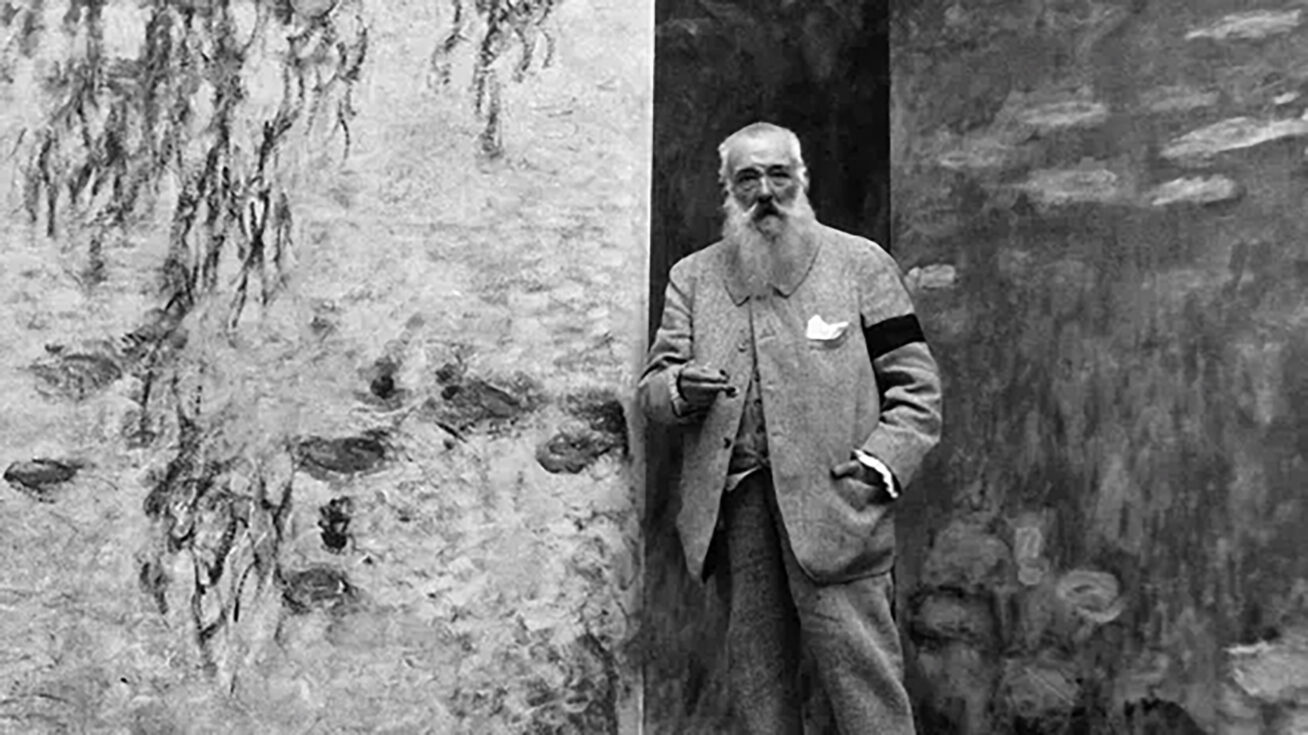

Photo by Jean-Pierre Hoschedé.

With the introduction of paint tubes in 1841, the popularity of painting outdoors, called en plein air (French for “in the open air”), increased. It quickly became a fundamental feature of Impressionism. Claude Monet was a lifelong advocate of plein-air painting. He spent hours at a time observing nature—the way colors reflected on water at different times of day and the way the clouds changed. In Waterlilies, Monet sought to capture the constantly shifting relationships between light, water, reflection, and atmosphere. The resulting effect positions the viewer simultaneously over and in the space: there is no indication of the horizon or pond bank to ground the view. The ideal was to capture a moment, not the details.

The photo above shows Monet in his gardens at Giverny sitting next to the waterlily pond while working on PAM’s Waterlilies. A large white parasol keeps the sun glare off the canvas. Next to him is Blanche Hoschedé, his daughter-in-law and stepdaughter.

Monet’s technique

Brushwork

Monet used a number of different brushstrokes and techniques to create Waterlilies. By this point, his brushwork had become markedly freer and more liquid. He used long vertical strokes to describe the reflected willow branches and swirling, circular strokes for the sky and lily pads. Juxtapositions of blues and yellows (complementary colors) heighten each color’s intensity.

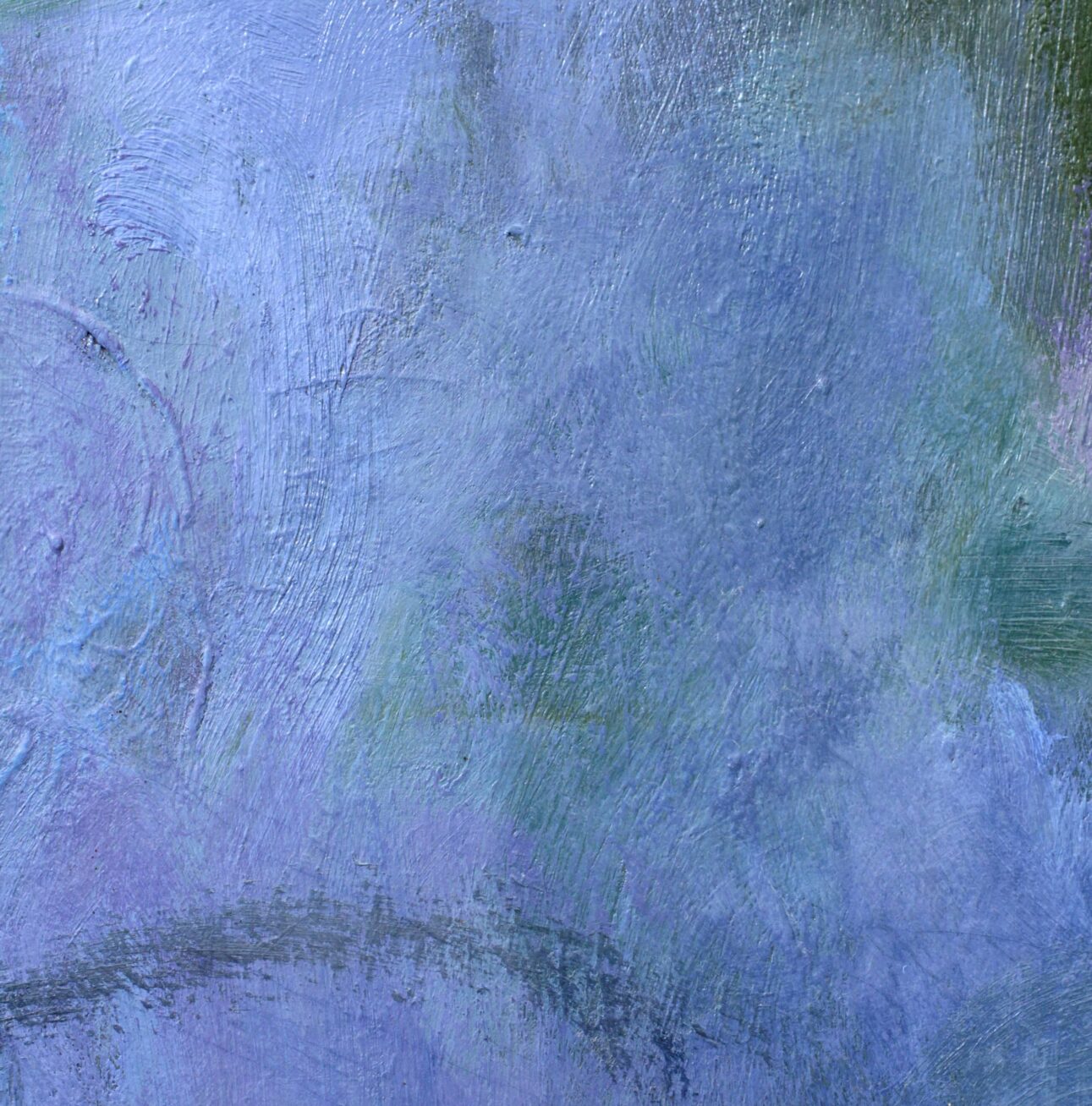

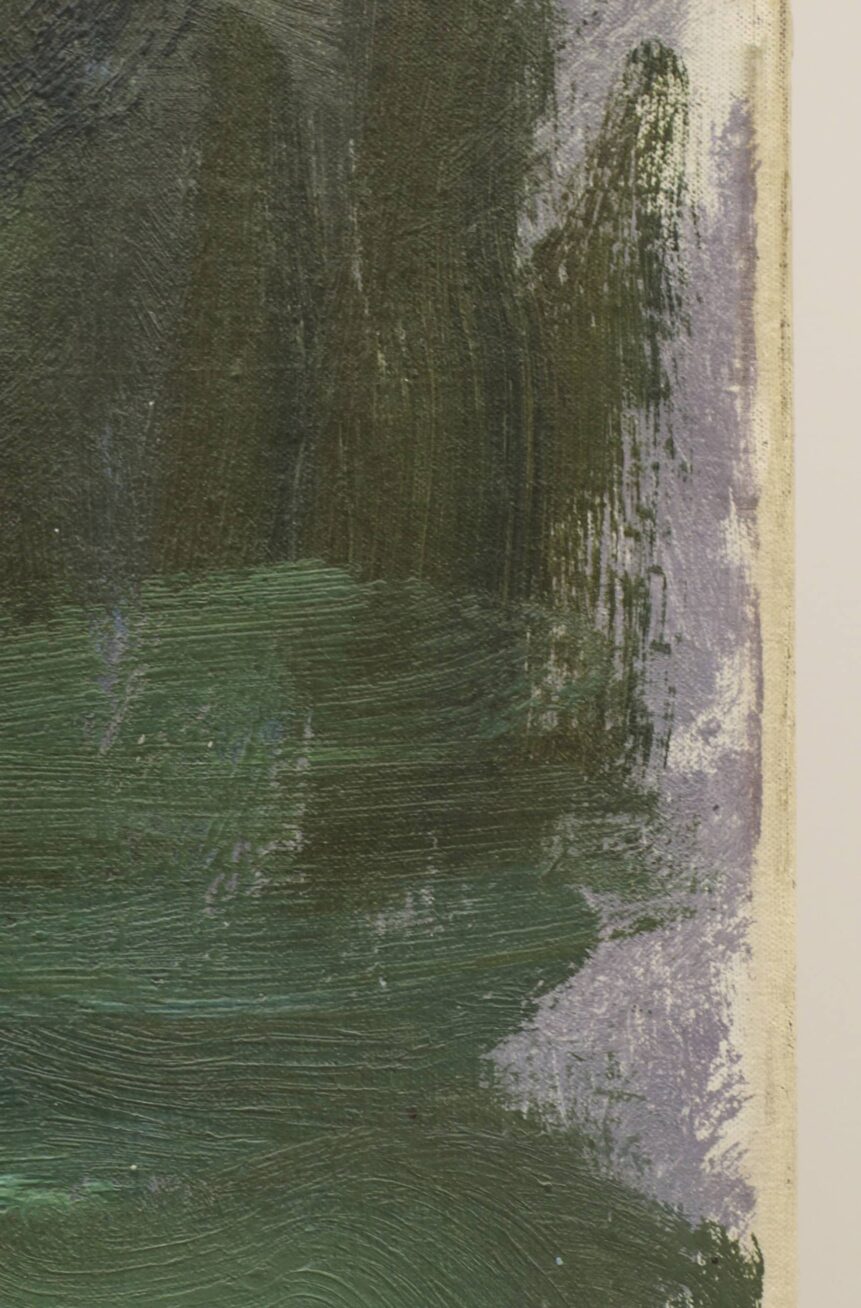

Blocking in

Monet did not use underdrawing, which are sketched lines made by a painter as a preliminary guide; rather, he blocked in the main fields of color with thinner washes of transparent, dilute paints, as in the lavender color at right. Monet’s handling of the paint was loose and rapid.

Wet-in-wet

Monet created the reflections of weeping willow branches by mixing vivid colors directly on the canvas. He applied successive brushstrokes while the paint was still wet, allowing the strokes to mix in a fluid way that produces no hard edges.

Layering

Monet did not paint the water first. The brilliant blue of the sky reflected on the water’s surface was created with sweeping, opaque brushstrokes, but here we see the blue stroke was pulled over the green of the reflected willow branches. This indicates that the blue was applied later.

Impasto

In the later stages of painting, Monet applied the paint thickly in fluid, sweeping brushstrokes to create the waterlily flowers. Delicate paint peaks are visible in the areas of green and white where the loaded brush was lifted from the surface. The flowers were originally painted in violet tones; later, he applied cool blue and green on top of the violet in the upper half of the painting.

Drybrush work

Fragmented blue and violet brushstrokes make up this round shape. Thick paint was dragged over dried lower layers, resulting in a broken-up brushstroke that skips over the surface of the underlying paint.

Tache

Although Monet had largely abandoned his use of short, loaded strokes of color, called taches (French for “blots”), by this time in his career, we see echoes of this technique in the pink water lilies in the lower half of the painting. He used a flat brush to apply quick dabs of thick, pure color. These blossoms have minimum detail; he focused instead on intense colors and general shapes to capture their essence.

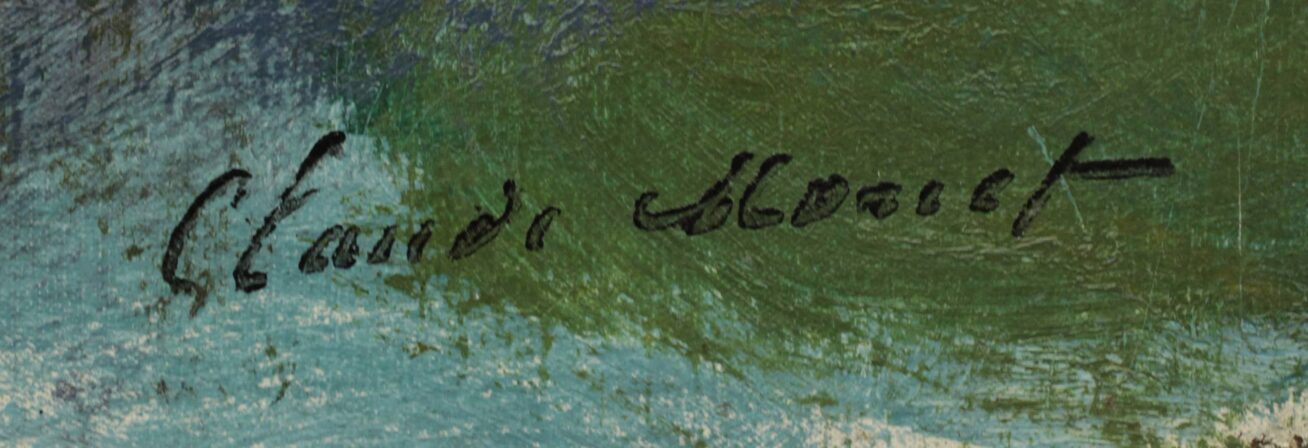

Signature

Waterlilies has a signature stamp. This is because Monet kept this work in his private collection. He would typically sign only works that were going to his dealer for exhibition or sale. After he died, his estate created a stamp used as a means to indicate authenticity.

Videos

The restoration and related programs are supported in part by a generous grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project. Waterlilies is one of 24 globally significant artworks to receive conservation funding support this year from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project program, which has supported the conservation of more than 260 individual pieces of art across 40 countries since 2010. The program previously supported PAM’s conservation of Roy Lichtenstein’s sculpture Brushstrokes in 2019. Read more about Bank of America’s support.